Book Review

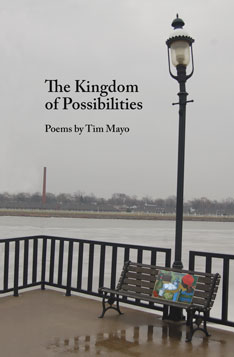

The Kingdom of Possibilities by Tim Mayo. Bay City, MI: Mayapple Press, 2009. $14.95.

Reviewed by Lisa Vihos

In The Kingdom of Possibilities, Tim Mayo introduces us to a sensitive, thoughtful, complex speaker. The voice in these poems is consistently the voice of someone trying to find an answer to the perennial question, “why am I here?”

In this case, as in most, there are some complications. In the poem “Nineteen Forty-Five,” the speaker ponders his own conception:

a man and a woman untwist from the bedclothes

gasping for something the humid air can not surrender.

The two people responsible for the existence of the speaker in this poem were strangers, who reached out to each other during wartime, staving off the “loneliness death fosters.” They couple without forethought as people often do, and the results were disastrous, miraculous, and to be expected:

and they know there is no future—except

that something (now writing on this page) sperms

and squiggles in her belly

Mayo keeps giving us clues about a life, some life, no doubt pretty much resembling his own. According to what the poems tell us, it is a life that involves having been raised by adoptive parents, leaving home an angry young man, a fair amount of travel, at least two marriages, one child, a grandchild, a tendency toward Zen, and numerous passions.

Despite a clear sense that the poems are autobiographical, Mayo keeps the confessional aspect of his words in check. He shares confidences with us, but he does so subtly. He does not beat us over the head with his experience. Instead he gives us quiet moments that stir empathy; for example, in “Honey” the poem’s speaker stands at the grave of his birth mother, asking questions of origin in the second person, drawing the reader in:

What does one say at the grave of someone so

important you wouldn’t be here except for her

and the choices she couldn’t make… How in your life

you must thank her for the accident of your birth—

what does one say at such a stranger’s grave?

In the second stanza, the poet inserts “I,” making us more aware of the possibility of this being a personal story and the speaker as someone who has been attempting to speak to this mother for quite some time:

I try to whisper a few words. Dry, fine as pollen,

they still catch in my throat.

Mayo’s poems speak of a desire to connect and be connected, to be part of a family, whether biological, adoptive, or poetic. Mayo reminds us that the poet, by virtue of connecting the dots of past to present, gets to be part of a larger, more comforting scheme, even when circumstances may have left much to be desired. In “The Last Gift,” Mayo writes:

People tell me I’m one of a kind—I mean

how many poets do you know who’ve donned

the ineluctable mantle of the eternal present?

Is he poking fun at himself? Yes. Is he serious? Again, yes. Mayo seems to be telling us that poems are born in the present and the poet is here to catch them when they arrive. They may be drawn from the joys and scars of the past, but it is only in the now that they can be conceived and launched. Mayo’s poems are surprising. He invites the reader to repeat readings, and to the opportunity—through his evocative and well-crafted musings—to be born with the poet in the present again and again.

Lisa Vihos worked for twenty years as an art museum educator and is now the Director of Alumni Relations at Lakeland College. Her poems have appeared previously in Verse Wisconsin, and in Free Verse, Lakefire, Wisconsin People and Ideas, Seems, and Big Muddy. She resides in Sheboygan and maintains a weekly blog.