Book Review

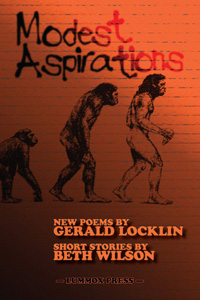

Modest Aspirations: New Poems by Gerald Locklin, Short Stories by Beth Wilson. San Pedro, CA: Lummox Press, 2010. $15.00.

Reviewed by Lou Roach

Gerald Locklin is a long-time favorite poet of readers of the many small-press magazines, as well as being known to the world of publishing in general. Author of many books, he is a Professor Emeritus of English at California State University at Long Beach, where he continues as a part-time lecturer. He also participates in the Master of Professional Writing program at the University of Southern California.

In this newest collection, he presents clear-cut opinions on subjects such as the state of the modern world,the complexities of writing over a period of many years, music, art, family and several other topics that are not easily categorized. Locklin writes out of a background rich in experience as a humanist extra-ordinaire. His observations of others range from humorous to somber, from irony to deep appreciation of the genuine in people, art, literature and music. His base of knowledge about life, from its best to its worst, is vast.

His in-depth comprehension of the fallibility of human beings is significant. His poems come from what he knows and he knows a great deal. Locklin, who has been labeled a “hobgoblin of American poetry” by his biographer, Michael Basinski, spent much time with underground poet Charles Bukowski. Theirs was an enduring friendship. In “More Unsolicited Advice to the Young,” he warns:

The Elizabethan sonneteer, Michael Drayton,

Instructed himself and us

To look in our hearts and write.He said to look in ours,

Not his or Charles Bukowski’s.

The California poet, who has also built a strong reputation for writing potent short stories, often approaches his work from a wry perspective. His poem, “Carpe Noctem,” tells the reader:

We are always being urged

By our parents and teachers

(Who don’t really mean it)

To be less like sheep,

Not to follow the leader

But to think for ourselves.. . .

I know what is meant by that,

But I’ve always cautioned my writing students

Not to think too much,

. . .

But to let their instincts and unconscious minds

And the emerging sounds of the words. . .

Write a lot of the poem for them.

Especially the first draft.

In the same poem, he notes that Robinson Jeffers, Cummings and Bukowski

“. . .did not prize the adjectival part of the ‘rational animal’ either.”

Like so many writers of his generation, Locklin obviously understands what it means to have strong convictions about the role of artists, poets and photographers “In and out of the American consciousness.” His sentiments are described in “The Canker in the Rose”:

We have determinedly defeated ourselves,

Defaced ourselves,

Addicted ourselves to chemicals, ease,

Illusions, rationalization, Irony

(The Ironic Fist in the Velveteen Glove?).

We will die for nothing, and thus

We have rendered our deaths meaningless.

. . .

Ah well, ‘twas ever thus,

In Athens, Rome, Gay Paree,

Stiffnecked London and Berlin,

Weary Moscow—and after our fall,

The rise and fall of Beijing and Tehran

Will be mercurial.

This poet has a knack for segueing into one subject from a quite different one. The reader is almost unaware of the move. He demonstrates this in a number of poems, but with a piece concerning photographer Alfred Steiglitz, he moves quite clearly from “This multiplicity of images” of Georgia O’Keeffe, taken by Steiglitz, to the issue of how the work of a young writer may be compared to poems written as

he grows older. He likens this to how the appearance of a camera subject changes as that person ages:

But why should a sixty-seven-year-old man

Be consistent with his twenty-five-year-old

Self? Why should this morning’s voice

Be the same as last evening? Why should we

Assume the younger man was wiser?

. . .

Should a writer never give voice to

Conflicting points of view?

(“Alfred Steiglitz: A Portrait: Georgia O’Keeffe, 1918, photograph”)

This compilation of Locklin’s contains only a few selections that refer to family. Two of those examples, “Vanessa Bell: Charleston Garden, 1933” and “My Finest Moment,” give the reader a glimpse of those relationships. That he values family is certain. A third poem, “The Berlin Wall,” leaves the reader with a question concerning the ambiguity of his feelings about marriage. I will leave it to the interpretation of his readership.

Locklin talks of visiting the home of “Vanessa Bell,” in England in his poem of the same name. He admits that while his wife and daughter explore the cottage where her portrait is displayed, he and his son “killed time in the garden.” They obviously did so with patience and understanding. We learn that from Locklin’s

own words:

the woman garbed in rose

sews a lily garment

draped across her lap.

the sun breaks through the ample foliage

that lines the pathway to the formless door.

even the impressionistic sky/sea upholstery

of the chair the woman sits on

is a work of art.

everything about the place is.

. . .

my wife would love to be the woman in this

painting, with her life of art and crafts and

living but inhuman things.she’s read a tower of books about

bloomsbury and remembers them, she can

even keep straight their genealogy of morals,

the entanglements, arrangements, and paternities,

that always fail me in my literature classes,

as futile as teaching lie and lay.i’ll never be able to give her charleston farm.

not to mention sissinghurst or knole, but

she’s turned our modest home into a poor-man’s

(woman’s) monk’s house, and made me assent

to the possibility of a return,

five years from now, when she retires,

to england and wales (where i taught a term

in l989: we lived in menai bridge and gazed

across the straights at bangor and snowdonia).

. . .

And i’m afraid i may be fool enough to do it.

In “The Berlin Wall,” he muses initially about seeing a picture of Mikhail Gorbachev in an advertisement, then recalling how he thought of the wall that separated East and West Germany:

. . .

But I was surprised once again

By how low the wall actually was.

I bet there were players in the NBA

Who could have leapt it.

But how few of the oppressed ever did manage

The escape to freedom?

It took us a quarter of a marriage

To erect our own Berlin Wall.

I always thought that one day

We would tear it down.

We never did. And now, two days before

The New Age of Hope, I know our Berlin Wall

Will withstand it.

With many volumes of poetry to his credit, I am certain that others contain more depictions of family. The number of poems in this book that spring off ekphrastic work is interesting and well-constructed, but I want to know more about Locklin, the man, rather than Locklin, the devotee of museums. “My Finest Moment” speaks to the writer’s devotion to one of his daughters:

I’m shopping at my youngest daughter’s

Favorite jewelry store…Luna in Belmont Shore—

For her 30th birthday, a little something extra..

. . .

I’m attired as usual like a homeless guy.

In front of the display case, a chic salesgirl joins me:

“What is your price range, Sir?”

And for once in my life, just this once in my life,

I allow myself the arrogance of answering, quietly,

“I don’t see anything that’s not within it.”

Gerald Locklin’s poems are seldom ordinary. He paints collages of images with his words, uses illustrative and concise language, and never condescends to his readers. If you’re not familiar with his talent, go now to the nearest bookstore for your first exposure. It will not be your last.

Lou Roach, former social worker and psychotherapist, lives in Poynette. Her poems have appeared in a number of small press publications, including Main St. Rag, Free Verse and others. She has written two books of poetry, A Different Muse and For Now. She continues to do free-lance writing, although poetry is her favorite thing to do.