Interview with Kimberly Blaeser

By Wendy Vardaman

Kimberly Blaeser, a Professor at University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee, teaches Creative Writing, Native American Literature, and American Nature Writing. Her publications include three books of poetry: Trailing You, winner of the first book award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas, Absentee Indians and Other Poems,and Apprenticed to Justice. Her scholarly study, Gerald Vizenor: Writing in the Oral Tradition, was the first native-authored book-length study of an Indigenous author. Of Anishinaabe ancestry and an enrolled member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe who grew up on the White Earth Reservation, Blaeser is also the editor of Stories Migrating Home: A Collection of Anishinaabe Prose and Traces in Blood, Bone, and Stone: Contemporary Ojibwe Poetry. Blaeser’s current mixed genre project, which includes her nature and wildlife photography as well as poetry and creative nonfiction, explores intersecting ideas about Native place, nature, preservation, and spiritual sustenance.

Blaeser's poetry, short fiction, essays, and critical works have been widely anthologized in national and international collections with pieces translated into several languages including Norwegian, Indonesian, Spanish, Hungarian, and French. Translated works have also been included in exhibits and publications around the world, most recently in Norway and Indonesia.

Blaeser, who has lectured or read from her work throughout the United States, Canada, Europe, and Asia, has been the recipient of awards for both writing and speaking. Among these are a Wisconsin Arts Board Fellowship in Poetry and a Writer of the Year Award from Wordcraft Circle of Native Writers. Her poem “Living History” was selected for installation in the Midwest Express Building in Milwaukee, one of her talks was chosen by Writers’ Conferences and Festivals for inclusion in the organization’s anthology of best lectures, and she was chosen to inaugurate the Western Canada Lecture Series. She is a past vice president of Wordcraft Circle of Native Writers and Storytellers, and currently serves on the advisory board for the Sequoyah Research Center, and on two American Indian Literature series boards for University presses.

A former journalist, Blaeser continues to indulge her interest in nature photography. She lives with her husband and children in the woods and wetlands of rural Lyons township Wisconsin and spends part of her year in a remote cabin in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. Other ongoing projects include collaborating with her son and daughter on books for children and a mixed-genre collection, Tinctures of a Family Tree.

WV: Tell me about ecopoetry. How is it different (or is it) from nature poetry?

KB: For me, what distinguishes ecopoetry from nature poetry is the embedded understanding of responsibility. Or response-ability, as I like to characterize it, so that the word suggests a relationship. That relationship involves a spiritual vision, being responsible by being engaged in the life processes. This aligns with a Native idea of reciprocity, a give and take relationship. And this active involvement with an alive world space— our responsive action, fuels our growth—our abilities. The more we pay attention to the natural world, the more we understand it; the more we understand it, the better able we are to act appropriately in a fashion that will help sustain all life. As fellow habitants of this world space, we live implicated in the state of the universe. A poetry that proceeds from or reflects this understanding is, in my view, ecopoetry. Now the poetry might be engaged in a simple act of attention or it might be involved in a more activist endeavor—critiquing dangerous practices or inciting involvement in political endeavors, but ecopoetry as I define it arises from an awareness of the entwined nature of all elements in our world, has as philosophical foundation an understanding of the interdependence of universal survival, and carries within it a sense of accountability.

And, of course, it alludes to or embodies this awareness through or within the aesthetically charged language of poetry.

WV: With respect to your own poetry, do you prefer the term ecopoetry, or are you writing nature poems or post-pastoral ones?

KB: Of course, not all my poetic work is of the same tenor, nor do the various pieces succeed to the same degree poetically. But I do strive towards writing that voices respect for the natural world and that attempts to incite a similar response in the reader/listener. Although I don’t weigh this in the writing of each poem, overall I think it fair to say I aspire to create poetry of spirit and witness, and many times the focus involves various kinds of survival, including ecological survival. On the journey toward that vision of sustainability, I think the writing wanders through several dimensions, crossing literary boundaries of what is being called post-pastoral, ecopoetry, and spiritual poetry (maybe also sharing some qualities of the contemporary metaphysical tradition).

WV: Do you think of ecopoetry as primarily an artistic/aesthetic movement, an ethical one, neither, or both? Does being an ecopoet require activism?

KB: Both/and. You knew it wouldn’t be either/or! Seriously, coming out of a Native literary tradition which includes ceremonial songs and song poems, I always expect poetry to “matter.” Indigenous literatures often have what I call “supra-literary intentions.” The writers/performers want their works to come off the page and do something in the world. In articulating this aesthetic that involves both art and activism, I often invoke Seamus Heaney’s discussion in The Redress of Poetry in which he claims a vision of poetry as both affective and effective, seeing it as “joy in being a process for language” as an “agent for proclaiming and correcting injustices.” I also love Linda Hogan’s expression of this duality in her poem “Neighbors” in which she writes both “This is the truth and not just a poem” and “This is a poem and not just the truth.”

So I do think it involves activism. The range of what this might entail is vast. It could be demonstrating, cleaning up natural sites, doing animal rescue, writing letters, voting. And it is important to remember that in some circumstances even to speak is a revolutionary act. Indeed, writing political poetry in an environment that sees that as an anachronism might also be considered activism.

WV: Does ecopoetry demand activism from its readers, too?

KB: I think ecopoetry asks of its readers/listeners for change. Some works demand more specific or greater activism. Allison Hedge Coke’s recent book Blood Run asks readers to participate in various ways in protecting a snake effigy mound in South Dakota and a portion of the book proceeds go to the cause. Linda Hogan’s work often rhetorically incites the readers in phrases such as “Get Up, Go AWOL!”

On the most basic level, I think all ecopoetry asks for change. Poetically it works to alter the reader’s vision or understanding. Such heart change should bear fruit in attitude and action. I remember a poem by Mary Oliver called “Red.” The poem is a simple narrative in which the speaker confesses her longing to see a gray fox. In separate incidents she encounters two, each hit by a car, each dying as cars continue to flood by. Hence the gray fox becomes the red of the title, red like the spilled blood of each. As the narrator witnesses the death of the fox, the reader witnesses her soul change—from one who desires to “collect” the experience of seeing a gray fox to one who mourns the callousness with which they are being destroyed.

So perhaps the poet becomes the “seer,” (and I mean that in both senses of the word). Through the images and detail of the poetry we can see in all their wondrous beauty places, elements, cycles, and creatures of the natural world. And the poet might also become the vehicle by which we can vicariously learn to see differently, they may become like the prophetic seer of ancient times who reveals, unveils, predicts, or even warns. Ecopoetry asks that readers take heed of the re-visioning they are offered.

WV: Are there particular themes or images that characterize ecopoetry? I’m thinking of the dissolution of boundaries and the permeability of boundaries, for instance, in much of what I’ve read—there’s a lot of transformation, as well as an exploration of human versus non-human.

KB: Thinking of this tradition in poetry, I believe the ideas of transcendence and transformation both play a key role in the philosophy. In my own work, the notion of correspondence is equally important as is the understanding of time as a limited linguistic construction. I think all of these suggest the permeability of boundaries you have alluded to. They suggest a comingling, and invoke or become a strategy or pathway for discovering the eternal, the ephemeral, the immaterial. And, although some works do set up a kind of human/non-human dichotomy, I most admire works that tend to undermine the supremacy of the egocentric and individualistic. I think of a slight poem by Chinese poet Li Po. In the translation I have, the title is “Zazen on the Mountain” and the last two lines read: “We sit together, the mountain and me, / until only the mountain remains.”

WV: Are there any forms, structures, or aesthetic elements that characterize ecopoetry? (The haiku, for instance, seems particularly important.)

KB: Just as in the Li Po poem the ego disappears, in haiku even the language of the poem dissolves into experience, or some would say into enlightenment. I have a great affinity for haiku and I love to write them, but I have to say—and this is not false modesty—I am by no means a master of the form. But because I am so enamored of the practice, I do often write haiku. Poetically, that striving after simple image is a wonderful discipline; and the spiritual discipline of Zen often associated with haiku also enriches the haiku quest.

In regards to other themes and forms, I think the object poem and the ode have also been used to good effect by ecopoets. We find fruitful predecessors in some of Neruda’s odes, odes that center on the chestnut or a yellow bird but, in so doing, gesture to much beyond, to the order and chaos and larger beauty and mystery of the world, to the smallness of the chestnut, the bird, and, yes, to our own smallness. Other times (as in the “Red” poem mentioned above) the narrative form is used as the speaker of the poem relates an experience that leads to personal change. And I would point to similarities shared with naturalists or natural history writers. In this vein, the listing poem is sometimes employed, as a catalogue or accumulation of details provides, for example, a feeling for the essence of a particular place.

WV: A few of the names I often see mentioned in connection with ecopoetry nationally include Mary Oliver, Wendell Berry, Joy Harjo, W.S. Merwin, Gary Snyder, Pattiann Rogers. Which poets do you think of or particularly enjoy, and who would you recommend to a reader that wants to get an idea of what ecopoetry is?

KB: I’m a bit eclectic in my gathering of poets. I am a great fan of Mary Oliver and Joy Harjo, both of whom you mention and whose styles differ quite dramatically. But I am entranced by both. Oliver’s West Wind, for example, blends so lovingly the intricacies of nature and the poetic calling, sometimes achingly and almost in the ecstatic tradition. Joy Harjo is often a poet of grit and, as she says, of “truth telling.” She is one of a handful of Native poets whose work has had an influence on the direction I’ve taken in my writing over the years. I don’t think I could aspire to the wild unfettered range of her imaginative vision, but I love the way she welcomes story and mythic reality into the everyday world, and the vigor with which she carries forth stories of injustice.

Other poets: David Wagoner visited Notre Dame while I was a student there and I have been grateful to follow his fine work. I admire the writing of Linda Hogan in every genre in which she works. Her life and her creative work are both filled with a dedication to the earth and all its inhabitants. There is an attention to detail and an overriding awareness of timelessness that I appreciate in the writing of Robert Haas. Like many people, I am fascinated by Coleman Barks’ translations (and performances) of the poetry of Rumi and much of this writing is filled with a kind of spiritual search interwoven with an evocation of the lushness of nature.

Because poets tend to address multiple subjects, in addition to following the work of particular poets, I find it helpful to keep my eye out for thematic anthologies. One that I found and have used in teaching several times is A Book of Luminous Things edited by Czeslaw Milosz (who I was also lucky enough to hear at Notre Dame). Poetry Comes Up Where it Can, edited by Brian Swann, is an anthology of works published first in The Amicus Journal and all the works deal with nature and the environment. Another anthology, Poems to Live By In Uncertain Times, edited by Joan Murray, includes among its larger gathering a couple of sections of works we could call ecopoetry.

WV: Does ecopoetry mean the same thing to a Native and a non-Native poet? Perhaps that’s a too broad and binary way to frame the question, but I’m curious in general about the extent to which the interest in “eco” right now is driven by Native sensibilities, and whether it is a co-option of them in any way?

KB: I’ve partially characterized the Native understanding of ecology when I spoke about the philosophy of reciprocity and response-ability. Whether for some practitioners the current literary eco-trend involves any kind of “co-option” of Native sensibility or a stereotypic amalgamation of complex and varied tribally specific systems of beliefs, I think the more interesting tension involves a divergence in origin or function—the crossover between acts of resistance and the literature of resistance.

Let me elaborate. Because historically Native people have faced destruction of homelands, removal, and land theft, I think the undertones in Native works often involve conflict and loss. Also, given the ecological devastation witnessed over the years from clear-cutting of forests to the decimation of animal populations like the buffalo to the pollution caused on tribal lands by mining and industry, the inheritance of oppression has fueled the need to assume a role as defender of the earth and of sacred lands. It might be fair to suggest that the literary eco-tradition in Native communities has arisen largely from political need while the eco-tradition in non-Native communities originated more as an aesthetic movement. I believe the two have come closer together in recent years and that important alliances have formed. A recent multi-genre collection, Colors of Nature: Culture, Identity, and the Natural World, explores these separate and overlapping traditions and stories.

The published work of Native writers such as Marilou Awiakta, Haunani Trask, and Elizabeth Woody includes examples of poetry that had its origin in ecological activism. In this complicated terrain, let me offer a specific instance of a poetic work that explores this eco-warrior stance as it pertains particularly to America, Native America, and the land that is home to both. Fight Back: For the Sake of the People, For the Sake of the Land, by Acoma writer Simon Ortiz, was published in commemoration of the Pueblo Revolt that took place 300 years earlier, but it also explicitly deals with uranium mining in the Grants region of New Mexico and the fallout from the atomic bomb detonation at White Sands. Although covering much other ground in these poems, Ortiz underscores the need for Native peoples to “fight / to show them” and for America to “give back” so “the land will regenerate.”

WV: Many of your poems about the natural world have strong narrative and spiritual components, and they tend to include people or animals who are sentient creatures. I’m thinking, for instance, of “Memories of Rock” or “Seasonal: Blue Winter, Kirkenes Fire.” Is that a fair way to characterize your approach?

KB: Yes, that seems an accurate representation. I admit I find it hard to characterize my own approach, because as artists and spiritual beings, we are always in a process or search for insight. I may ask or imply a similar question across a range of several poems, not only because I want a reader to contemplate the philosophical territory, but because I am treading there beside you, wondering too.

One tack I do recognize is my attempt to break down various classic demarcations. For example, the class line between what is alive and what supposedly inert matter. Even science no longer backs up the “dumb matter” assumptions.

Sometimes I use narrative in service of defamiliarization. Mythic depth or dimension allows us to imagine or admit an “other” range of realities. Perhaps it turns or changes the hierarchy, the power structure. Perhaps it allows for different ways of knowing, employs alternate languages, or dis-orders sense data. If we come back from such a linguistic journey with one small cog liberated from the “must-be machine” of our everyday, our experience of “reality” will change.

WV: In “Seasonal: Blue Winter, Kirkenes Fire,” you write: “So soul rest comes upon the Nordic land/ and upon its ancient reindeer people./ The tired water sleeps as ice/ and we glide upon its hardened body/ and slowly turn the earth with our prayers.” The notion that we do “turn the earth with our prayers” or that lands and people have souls seems to me one that could be offered sincerely within a Native worldview, but would more likely be meant ironically by a non-Native author. Is that a fair distinction to make?

KB: I am not certain the belief, understanding, or possibility implied only exists within a Native context. What is often generalized as a Western worldview might process the meaning differently, but not all non-Western sensibilities would do so. And, of course, poetic language itself is not strictly representational. The figurative ambiguity poetry suggests aligns with the complexity of what we call truth or understanding. Sometimes reality itself belies the dictates of logic.

So how do we or should we read such passages? Of course, we might engage in the fact/fabulism debate. Choctaw Louis Owens greatly objected when the term “magical realism” was applied to certain elements of Native writing, including his own novelistic representations of ghosts. For example, he writes that James Welch’s Blackfoot world was “rendered so completely. . . there is no disjuncture between the real and the magical, no sense that the magical is metaphorical. . . .The sacred and the profane interpenetrate irresistibly, and this is reality.”

I might suggest that a purely cause and effect view in regards to the above passage is too simplistic. The subtle interconnections between forces remain a mystery. We create stories or myth about the visible as a way of approaching understanding and helping us gain access to the invisible or ineffable. The meaning we garner may not come from a formulaic model of equivalency or logical sequence such as x equals y or x therefore y.

Barre Toelken tells of the questions he raised about the Pueblo tradition of removing the heels of your shoes in the springtime to protect the earth mother who is pregnant. He wondered if he kicked the ground it would mess everything up and keep plants from growing. The reply was inconclusive about the outcome; “I don’t know whether that would happen or not, but,” the speaker declared, “it would just really show what kind of person you are.”

Relationship requires ritual. Is it symbolic or does it have measurable consequences? On one hand, it certainly affects those who engage in ritual or ceremonial practices. Would it be naïve to suggest that in the context of science (as well story) we affect the fate of the earth? What seems untenable may sometimes be true. Can the Tibetan monks “think” wet towels dry. What of chaos theory and the butterfly effect?

All that is to say, maybe not. Maybe the gesture of that poetic language refuses to finally center on only literal or only metaphorical (or ironic) meaning or belief. Perhaps the outcome is really the question you ask—how might we understand this and what does it mean if we read it in these different ways? Maybe we stay in a state of questioning long enough to feel possibility. That is different than simple refutation of so called “facts.”

WV: Which Native American poets and writers would you recommend (contemporary or otherwise) as a good beginning for someone who hasn’t read much Native literature?

KB: I’ve already mentioned several: Linda Hogan, Simon Ortiz, and Joy Harjo are three internationally recognized contemporary Native poets. I’ve also spoken about Allison Hedge-Coke as a strong eco-writer and she is fast gaining recognition. There are a host of other wonderful poets. Among the well-established are N. Scott Momaday, Louise Erdrich, Gerald Vizenor (mainly for haiku), Joe Bruchac, Jim Barnes, Luci Tapahanso, Carter Revard, Sherman Alexie, and Ofelia Zepada. Some strong younger or more regional poets include Heid Erdrich, Mark Turcotte, Margo Tamez, Armand Ruffo, Denise Sweet, Laura Tohe, Gordon Henry, Janet McAdams, LeAnne Howe, Eric Gansworth, and Gloria Bird. Still younger break-out writers right now include Sherwin Bitsui, Santee Frazier, and Brandy McDougall. There are many more whose work I admire and I’d like to refer you to a longish essay of mine on Native poetry, “Cannons and Canonization: American Indian Poetries Through Autonomy, Colonization, Nationalism, and Decolonization,” in The Columbia Guide to American Indian Literatures of the United States. It includes a bibliography of Native poets up to about 2005. There is a wonderful rich tradition in Native poetry and almost every writer can be read in conjunction with the tradition of ecology of land, mind, and spirit.

WV: Appreciating the sophistication of writing that isn’t familiar often requires new knowledge and the willingness to move in different directions, even to expand our notions of what poetry can be. I’m thinking for instance of different aesthetics, the significance of oral tradition, uses of humor, the dividing line between prose and poetry. Are there any differences that would be particularly helpful for readers to be aware of when they first come to Native poetry?

KB: I think it might be accurate to describe the earliest years of Native poetry publishing as a “movement,” or the poets as forming a particular “school” of writing. That is not to say the Native writers were not also aware of or engaged in the larger American or world poetry movements. There were, however, political, literary, cultural, and personal interconnections in their work; and, taken together, the writing of these and subsequent indigenous poets attest to the possibility of a “Native Poetics.” Infused with echoes of the song poems and ceremonial literatures of the tribes, born out of indigenous revolution, filled with the dialogues of intertextuality, sometimes linked to the cadences and constructions of “an-other” language, marked by the symbolism and ethical considerations of “an-other” culture, replete with mythic and intergenerational narrative, frequently self-conscious of expectations placed on Native literature, and often resistant to genre distinctions and formal structures—the works do suggest a certain literary sovereignty and an attempt to create a community-based literature.

Each of these qualities in themselves are more complex. The choice of language—Native, English, mixed—for example clearly impacts sound and structure. Often the intertextuality results in a multi-vocality; the mythic grounding in an implied dual-narrative. Cultural conceptions like those regarding time, dreaming, or ideas of good or bad behavior influence the ontological reality in which a poem exists and also how it “means.”

Perhaps one aspect, the link to oral tradition that you allude to, is most readily understandable. If the work arises out of a performative tradition or the poets are heir to or participants in such a Native tradition, the impacts might include: ultra-sensitivity to the spoken or heard quality of the poem; expectations for the engagement of the reader/listener; and attempts to suggest the layered quality of ritual or ceremony by the inclusion perhaps of vocables, song, drum sounds, etc. Peter Blue Cloud, for example, has several poems that include two parts presented in separate columns on the page, thus suggesting the simultaneous spoken, one score perhaps performing as a chorus. Often poems employ space, absence, and various kinds of gesture to leave room for the participation of the audience in the “making” of the art or the “making” of meaning.

As is true of reading any poetry, the more you bring to the page regarding origin, specialized language, symbolism, etc., the more fulfilling will be the engagement with the piece. Native poetry is often readily accessible on certain levels and its beauty and complexity grow with our ability to appreciate or understand other levels of performance or meaning.

WV: One difference that’s gotten a fair amount of attention is the relative emphasis on poetry as “original” and “individual” in Western art and literature, as opposed to being the collaborative product of a traditional community. Is this a valid distinction to make? (I sometimes think that Western Art is much more collaborative than many of us were taught—I always think, for example, of the Renaissance studio as a model for artists working together in visual art). Are we starting to appreciate collaboration more than we used to?

KB: I alluded to this a bit in talking about multi-vocality, performativity, and dual narrative. But on a philosophical level the sense of “carrying” the story rather than “creating” it impacts a poet’s stance. This idea of ongoing telling is most readily apparent in works that verbally declare “That’s what she said” or that include the other voices or telling within the current version. One of my own poems I build partly from lines of other contemporary Native poets and in the epilogue of Absentee Indians I actually tell the story of one particular collaboration by Native grade school students. Of course, the idea of “author-ity” is diminished in such practices. Some might find this problematic. But I have seen in Native poetry, not the “anxiety of influence” written about by Harold Bloom, but instead a “celebration of influence.”

My own sense is that this community space and the community-based art that ensues from it has experienced a resurgence throughout the U. S. in our lifetime. The eat local, vacation local, and in UW-Milwaukee’s case, read local movement is flourishing.

WV: Cave Canem has been very successful as an organization that promotes and develops poetry within the African American community—is there anything comparable for Native writers/artists?

KB: Since the creation of “Returning the Gift,” an international Native writers’ festival, the first of which was held in 1992, there has been an adjunct organization called Wordcraft Circle of Native Writers and Storytellers. Together these two have fostered Native writing in a variety of ways including through mentorship, an online community, a newsletter, some publications, and regular regional and national gatherings. In conjunction with these two groups, an annual competition is also held for a first collection of poetry and and a first collection of fiction, with the awards including publication of the works. Plus there is an informal community of Native writers who work together within the AWP and there are a two major Native writing centers: the En’owkin Center in Penticton, British Columbia and the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. Together these organizations and community groups have been largely responsible for fostering a new generation of Indigenous writers in the Americas. By the way, plans are underway to hold the 20th anniversary Returning the Gift festival in Wisconsin in 2012.

WV: Are there barriers to Native American poets publishing and finding an audience? What can we do to change that?

KB: Native poets and poetry face many of the same obstacles that plague other “minority” literatures, especially romanticized image and stereotypic expectations. Society at large, influenced by classic westerns, captivity narratives, and familiar images like those popularized by Edward Curtis, has a simplified idea of what “Indian” literature should be. If the works do not fulfill these romantic and often over-generalized expectations, they may not be seen as “authentic.”

There are also often special series for publishing Native work and publishing houses may resist their inclusion in regular releases from the press. Native writers might be included in special issues of journals more readily than in the normal yearly cycle or their submissions might be expected to always arise out of some aspect of their Native identity. Nominations for awards, too, are often for those that include the word “minority.” This pigeonholing happens to poets of every persuasion, but perhaps more frequently to poets classified by race.

The question this raises involves tenets of evaluation: what makes “good” poetry and does “beauty” or “goodness” differ significantly in a Native tradition as compared to a Western one? Can the work of Native poets meet standards set by one or another awarding agency? If so, does that mean it acquires the particular patina required by the awarding agency, or that the awarding agency can recognize beauty in different aesthetic traditions?

Regardless of the answers to these questions, I think the tradition in Native poetry is strong and thriving. I am honored to be a part of this movement at this vital point in history.

WV: Are there any trends to watch for in Native American poetry? Are those similar to or different from poetry in general?

KB: There are some interesting thematic trends I have noticed. Among certain younger poets, there is a self-conscious rejection of the verbal kingpins that have signified much about a familiar and influential Native history. For example, the experiences of reservation life, removal, relocation, and boarding schools have informed much of the work by early and contemporary Native poets. Navajo poet Esther Belin employs the acronym URI for Urban Raised Indian, signifying a different experience from her predecessors. Comanche Sy Hoahwah crosses old mythologies with that of the new Indian Mafia.

Sometimes these new experiences have fueled experiments in form as well. The late First Nation poet Marvin Francis, for example, created a unique long poem, City Treaty, that includes text boxes, stage directions, a host of textual variations, and symbols from dollar signs to crows’ feet.

In general though, although there are new trends and interesting new voices, some continuities regarding cultural context continue. And these cultural continuities might also link Native poetry communities in the States with global Indigenous communities. I have witnessed rich cross pollination internationally among Indigenous writers.

WV: Tell me about how you became interested in poetry. Did you write poems as a child, and if you did, who or what inspired you to do that? How and when did you decide to become a “professional poet”?

KB: The love of language is in many ways a gift we inherit. I did write as a child and one of the strong influences on me came from the habit of the oral in my environment, my life within a family that performed story as an everyday act. Both my immediate and extended families at White Earth were filled with talented and colorful storytellers. I grew up amid people who not only made of the everyday incidents lively accounts, but who sang, recited, teased, imitated, read out loud—whose entertainment was often joyful verbal exchanges. Since poetry, especially, depends deeply upon the heard element of language, upon the music of voice, the rhythms of sound, spaces, accents, I think I was drawn to the genre partly by my fascination with the soundings of poems,

Although I wrote and published in various capacities and in different genres throughout my years in school, it wasn’t until 1990 when I did a short fund raising tour in Minnesota with Winona LaDuke and Gordon Henry as part of the White Earth Land Recovery Project that I began publishing as a poet. I had performed some creative pieces at our presentations, and was approached after one event about submitting to a small regional publication, Loonfeather. With that first publication and my participation in the 1992 Returning the Gift festival, I entered a wonderful network of writers.

WV: How did growing up with mixed Anishinabe and German ancestry affect your poetry?

KB: I have written about my German grandfather in a couple of poems, but my German grandmother died before I was born. Maybe because of her absence, or maybe simply because we lived on the reservation with strong connections to all my Indian relatives, the German heritage did not figure as strongly (as specifically German) in my life. There were certainly influences--German Catholicism, songs and smatterings of language, foods, etc., but my dad didn't think of himself as "German" in the way my mother understood herself as Indian. The language, too, was employed differently. My grandpa used to talk in German to my dad and his siblings about anything he didn’t want the grandkids to understand. So it was in some ways a “private” language. But in my Indian family, we were encouraged to learn and use the Ojibwe language.

Of course, the whole dynamic was more complex than those few statements makes it seem. My sense of being a “mixedblood” certainly arises from the circumstances of my family, and perhaps my dad felt his own heritage less welcome in some ways. I do know that as he aged he seemed to remember more, or perhaps he shared more as I encouraged him to tell me more. As he aged, his memory was also fitful. When I was to do a short reading tour in Germany, before I left I asked quite a bit about family origins and he was hazy. When I returned with stories of encounters around the Blaeser name, his memories seemed to come more clearly.

At any rate, I try to celebrate both. In poems like “Family Tree” that is clear. There is another poem, not yet gathered in a book, that is specifically about

the sausage-making tradition that comes from my dad's family, but hearkens after a meaning that has more to do with the making of community and memory.

WV: Who are some of your favorite poets or those who have influenced your work?

KB: I’ve named several of the established writers already in previous answers: Linda Hogan, Simon Ortiz, N. Scott Momaday, Joy Harjo, Pablo Neruda, Mary Oliver, translations of the haiku masters Basho, Issa, and Buson, translations of the work of Rumi, David Waggoner, Robert Haas. I read quite a bit of Baudelaire in translation and some in French when my language skills were better and certain of his poems have always stayed with me. I also grew up reading, hearing, sometimes memorizing long narrative poems like those by Whitman and Poe as well as work by e. e. cummings, Hopkins, Blake, Frost, and Dickenson. Once the language, cadence, and stance inhabit us, they stick. So that canonical background played together with or against poets on the margin has affected my work on many levels. Others poets include Dylan Thomas, Carolyn Forché, Jimmy Santiago Baca, Adrian Louis, and Louise Erdrich.

I’ve encountered some writers first by reading their poetry for a class assignment, others in the back room of some bookstore while scanning a stack of obscure small press books with faded covers. I came to the work of certain poets first by hearing them perform in association with particular events or movements. Of course, our affinities may change over time, but we still carry the cacophony of these diverse poems and voices. We never really know how they spill over into our own writing. Sometimes I consciously sit down with a poet or work in mind, quoting or alluding to it in my own poem. But we all know the influences also make themselves known even when we ourselves are unaware. I once received an email from a writer friend, frantic because he had sent a poem off and then worried it contained a line “stolen” from my work. So once again we are back to how we conceive of this intertextuality: anxiety of influence or celebration of influence?

Among my own influences are also some relatively unknown or regional writers—people I’ve worked with over the years as colleagues or in writing groups. And then, because my writing includes some mixing of genres, the influences, too, come from writers working in other genres. In recent years, I’ve also had some great opportunities to be a part of international events and know the writers I have encountered there have had great impact on the way I view my work and sometimes on the subject. One example: When I was in Indonesia, each event included local writers together with the touring international group. One night a poet from Jakarta prefaced his reading of a poem called “Going Home” by explaining that when he wrote it he had returned home after having been away for ten years. What he didn’t say was he had been in exile because of his political activism, his work for democracy in Indonesia. A haunting line in the poem has lived in my memory as image: a faded and tatter sign bearing his name and the message “come home whenever.” The memory of the poem, the image, the circumstances of the reading, the backstory, etc.—all these now always color my own reading or writing of poems about home places.

WV: Your own career has taken you to poetry, scholarship, fiction, playwriting… Do you have a favorite genre to write in? Do you consider yourself a creative writer or a scholar first?

KB: There has just been a conversation about Native creative writers as scholars or scholars as creative writers on the Studies in American Indian Literatures discussion forum. It reminds me of after I had my children trying to decide if I was a mother/poet or poet/mother. What I decided then and think also about my public work is the writing is all of a piece. The way I think about things and, therefore, the way I write entails all of what people like to classify as scholarship and what they classify as art. I’m tempted to say they are part of a continuum, but I don’t think even that is quite right because it still implies a kind of progressive line. In my own understanding they are both a part of looking deeply at the world. Although at times in order to meet expectations for publication or promotion I may apply myself to follow particular conventions.

Of course audience and impact differ depending upon genre. And then sometimes that elusive quality inspiration affects our course. Something feels like a poem or more specifically like a haiku moment. Some other image or experience might in our encounter of it require an-other form. Or we may choose to write about the same experience in different genres. I have written, for example, about the Anza Borrego in poetry and in creative nonfiction. The pieces each attempt (and I hope achieve) something different.

I love writing in various genres and bringing the genres together. Maybe it is like an athlete doing cross training. And I am oddly reluctant to declare an affinity for one. It would be too much like a mother naming a child her favorite. Although at this moment I am more accomplished or more recognized as a poet and as a scholar, I still enjoy writing creative nonfiction, dramatic monologues, short fiction, etc..

WV: One of the things I admire about your work is the way you bring together poetry, prose, and scholarship in poems like “Housing Conditions of One Hundred Fifty Chippewa Families,” which examines the political content of “facts” and numbers, and the way people’s lives are framed in research, or “Dictionary for a New Century,” which examines the definition of words in different cultural contexts. This mixture of scholarship and poetry seems to me a more prominent strategy in Apprenticed to Justice, as opposed to Absentee Indians, though there are some wonderful ethnographic poems there, like “The Last Fish House.” Could you comment on how and why you mix scholarship with poetry? Do you include the poetic in your scholarship, too?

KB: Yes, I do mix the poetic and other creative work in my scholarship, too. In general the writing I do as a scholar tends toward accessibility and avoids the competition to string as much jargon as possible in sequence! When you ask why I mix the two, I have to say honestly sometimes I don’t really know I am doing it until after the fact or until someone points it out. With the Hilger “Housing Conditions” poem, I felt her text had to be heard as one of the voices, not really thinking of it as “scholarship,” but as a speaking entity. Then, of course, the idea was to allow the reader to experience the contrast between these voices, between their perspectives. Juxtaposing the two, visually or verbally letting them rub against one another, creates a spark and this accomplishes a kind of critique. But some of that work has to be done by the reader. There is commentary, but there is also space for the reader to come in and “make” meaning.

I hadn’t thought of it in just this way before, but that poem is almost like staging a drama, allowing the reader to visualize two different people speaking. It also offers a kind of filmic dissolve where one image of place recedes into a very different one, depending upon the speaker. Now all that analysis was prompted by your question. I write in a more intuitive way. I know essentially what I want to achieve and have a strategy for approaching the piece, but eventually, as you know, the poems acquire a life of their own and we end up writing something we didn’t know we knew or revealing an insight we are incapable of ninety-eight percent of the time.

Sometimes if something is niggling at me, exploring it in poetry leads me to a better understanding of it as well. I had written an introduction to a new edition of the Inez Hilger book for the Minnesota Historical Society Press. It was the first time I encountered her work. In my short essay, I tried to suggest the layers of story inherent in the text, one of which had to do with the presumptions of ethnographic work done among Native peoples. But the book haunted me and haunts me to this day. Writing that poem helped me begin to come to terms with why. But I don’t really think I’m done working with the material.

WV: Apprenticed to Justice also mixes prose poems and poetry throughout and sometimes within individual poems, like “Shadow Sisters,” “The More I Learn of Men’s Plumbing,” and “A Boxer Grandfather.” What effect are you hoping to create with this mixing? Could you comment on the importance of story to your poetry?

KB: I come from a storytelling people and that narrative stance, the ideas of layers of story almost forming the very ground we stand on, or being “in the blood” as Gerald Vizenor suggests, informs all my work. I simply see the world through the lens of story. I have written recently about the inadvertent “cycle of stories,” a telescopic ring or “affiliation of stories” that seems a part of our basic identity. So I think I am approximating that way of being in the world: story as frame of being; story as frame of understanding.

Of course, another attempt that stands behind this focus in my writing is the simple wish to honor the voices and experiences of people overlooked in history or whose account of events have been systematically dismissed by certain people in authority. I am always at work telling an-other story, not the one on the ten o’clock news, not the one in older history texts. And, finally, I think I have the same passion to honor the sacred and the daily in the lives of ordinary people.

Philosophically, I might suggest that the narrative impulse and the poetic come howling from the same ache or hunger, some absence or loss, and therefore they remain entangled for me. Aesthetically, I could say that in Native culture the two always overlap. Sometimes consciously, as in “A Boxer Grandfather” I wanted to show the way story just spills into every spoken, into every daily experience. They come mixed in the world; they remain mixed in art.

WV: Are you also mixing the autobiographical with the fictional when you write poetry?

KB: Yes. I think my early work was more strictly driven by autobiography or community story, but unless a work or a feature of a work is presented as “factual,” I am instead always after “truth” and whatever will best serve it. That means some pieces are simply a work of my imagination. If, however, I am working with historical detail, I try to get it right to the best of my ability.

WV: Absentee Indians is written mostly in free verse, along with some haiku. Apprenticed to Justice includes prose poems, haiku, and concrete poems. Are there other forms, traditional or otherwise, that appeal to you?

KB: I remember a sweet moment from years back when I discovered that among those in attendance at one of my readings was a group devoted to writing pantoums. I had one in Absentee Indians and, when I shared it, I felt like one of the Magi arriving bearing gifts. They were so appreciative. I’ve played with that form since then as well as with blues poems and odes. Elements of the chant often seep into my work and I write list poems and some found poetry. I have been working on a series of Ojibwe alphabet poems. Many of the formal structures appeal to me as an aficionado of poetry, although I haven’t written them myself. Marilyn Taylor, for example, has a crown of sonnets that puts me in awe.

WV: You’re also a photographer. How has that interest come together with your writing? Do you ever bring them together or are they separate kinds of work for you?

KB: For some time I have thought particularly of haiku and photos as similar and photographic moments have led to haiku and other imagistic poems in the past. More recently I have begun to work with them together. I have been doing two kinds of ekphrastic work really: creating poems that interact with or accompany my own photographic images, and writing poems in response to older photos, especially family snapshots or stereotypic representations of Native people like those on postcard photos.

One of my projects for this coming year while I am on sabbatical is to learn more about editing software that will allow me to accomplish on the page what I have in my mind’s eye. Right now I don’t know how to manipulate the text or photo layout to achieve the outcome I want.

Of course, philosophically, there is a lot to be said about the aesthetic differences between text and image, but I do think in certain instances bringing them together can enrich the experience of both.

WV: A number of the poems in Apprenticed to Justice are political poems or poems of witness. (I’m thinking of “Red Lake,” for example, “Housing Conditions of One Hundred Fifty Chippewa Families,” “The Things I Know,” and “Who Talks Politics,” among others.) What’s the relation, for you, of poetry and the political, poetry and activism?

KB: I was in the Kingdom of Bahrain last October when the revolution that came to pass this spring was still festering. I was in Manana, the city where the main protests and crackdowns later took place. The people there talked poetry and politics in the same breath. One of the people jailed this spring for inciting violence and sentenced to a year in prison was a young female poet from that region. As long as speaking out is still considered a revolutionary act, poetry will have a role to play in politics.

If poetry is “the best words in the best order,” it makes sense that these well wrought phrases will impact listeners. Poetry can work in service of resistance.

WV: There’s a fairly stubborn strand of contemporary poets (I don’t know if it’s still the mainstream), perhaps more concentrated at universities than out in the community, who argue that poetry and politics don’t mix. Can language, can poetry, ever be “apolitical,” even in the apparent absence of political content? What do you teach your students about that?

KB: Emerson says, “It is not meter, but a meter-making argument that makes a poem.” The beauty of language and the ideas embodied in the language come together to create the poetry and this can be true of poetry on any subject.

This may seem odd, but with my students I talk about New Journalism and the revolutionary discovery writers came to during the Vietnam era that the idea of “objective” journalism was a fallacy, that everything was always written through an “I” and not just through some infallible “eye.” I talk about Norman Mailer’s Armies of the Night and do practical exercises in point of view, all aimed at getting them to “see” that we all “see” differently and that anything we write is always already colored by our particular perspective.

We also look at individual words and their connotations. All writing, after all, is inherently persuasive even to its most elemental selection of language.

WV: There’s a consciousness in your work of community and cultural change and what it means in your life—in for example, “Page Proofs.” Or in “Dictionary for a New Century,” when you write “At three my daughter kisses and releases her fish/ at four she asks if chicken is a dead bird.” The title (and final) poem of Apprenticed to Justice rehearses a history of community losses, and “Dictionary for a New Century” raises various questions: “Should we use or release our histories?/ Can education repay old debts?” How do you answer those questions for yourself? And how do you resist the impulse, in poetry and in life, to nostalgize and monumentalize the past without forgetting it?

KB: That is the one hundred thousand dollar question. I care to remember and to “re-member” or put back together in a fashion that allows or inspires others to do the same in their own lives. I tell my students that the specific will make your work more universal. I try to make my work alive enough that it can go with someone else and have a life I never dreamed of. Like the Indonesian poet Armarzan’s poem has with me.

My own writing about scorched earth campaigns, for example, arises out a particular history. My hope is that it touches those people who know about or have experienced that specific genocidal moment in America’s past, maybe making it more alive than it had been in their fifth grade text book or helping to heal the inherited memories of those who know that history intimately. But, sadly, scorched earth campaigns are neither an American invention nor a thing of the past. By poetic gesture, I mean to reach beyond that historic moment and these shores and to suggest something about the inhumanity of these practices in general.

There are ways and ways of writing about the past. Sometimes I might get it right, sometimes not. I keep trying.

WV: It seems to me that for a fairly small state, there’s a lot of separation among our poetry communities in Wisconsin—e.g., between university- and community-based poets, between Milwaukee and Madison, between page and stage. Is that your impression? Are some gaps more disturbing than others? Are there things we can do to bridge our differences, to promote communication and common interests?

KB: When I think about it, you are undoubtedly correct about the separate pockets of poets and poetry that exist in the state. But I have been fairly blown away by the sheer mass of poets we have in the different enclaves in Wisconsin and, naively, I guess have not given much thought to the economic, political, geographical, or philosophical circumstances behind the separation of the different organizations. Having been isolated as a Native writer in my years as a student, I now have writerly friends and cyber-writing groups and university colleagues and talented graduate students, and amazing writers I encounter while traveling, so am fairly feasting in community.

In my early years at UWM though, some of the minority students felt their work was not understood or accepted in the classroom and I became the faculty advisor for a writing group we called Word Warriors. Indeed, during that time I remember once being invited to visit a colleague’s class and then having it revealed to me by one of the students that I had been billed as a “street poet.” I rather liked that tag, although I know I should have shown proper outrage. My own sense is that things have moved in the right direction since that time period and we have a much more diverse population among our creative writing students.

Word Warriors went on to have a long history, membership fluctuating due to people graduating and moving away and, over time, the focus changed and we became a sort of “alternative” writing group and now have continued as a cyber haiku group. But through my experience with this group and then through the experience of Native writers nationally, I can relate to the comments you make about these almost class-like separations of poets.

One more related memory: being invited as faculty for a week-long poetry program in Ann Arbor and arriving, only to discover, the majority of students there were slam poets. I didn’t think what I had prepared would be appropriate and I called a writer friend with a “poetry emergency.” I also was a part of an orality conference in Canada were I was able to see some truly innovative performance poets.

So I realize there is a fairly wide divergence in how we all practice poetry. I think some people will remain closed to anything that doesn’t fit their idea of “proper” poetry, but your publication, the poet laureate recognitions in the state and communities, the national “Poetry Matters” campaign, UWM’s own “Eat Local, Read Local” and Poetry Everywhere videos, together with other public poetry projects, all go some way toward bringing poetry into the everyday and expanding awareness. There is a One Hundred Thousand Poets for Change about to happen (or will have happened by the time this is printed) that promises to be another way to bring poets together in communities.

WV: Do you think the university is the best place for a poet to be? Does it matter how poets earn their living?

KB: My experience may not match most university poets, since I spend a great deal of time in various non-academic settings. In general, I think writers who have vested interests in something—medicine, whaling, education, whatever—will have more to write about and write with more insight. The best place for one writer might scare another into silence. So we all have to find our places and not be afraid to shake things up if our needs change.

WV: Do you ever feel isolated or at a disadvantage as a writer living in the Midwest? Have you spent time outside the Midwest?

KB: Because I have a sense of belonging to place and take great joy in the natural areas in the Midwest, I do not feel isolated in any way. I realize that the two coasts are seen as more vital in terms of poetry, but I have no desire to move. I travel often, though not for long periods of time. What I like most when I travel are not the great cities, but the experience of the rural in other nations.

WV: Do you have any ties to writing communities in Minnesota, where you grew up?

KB: No, I have ties to individuals, some of whom are writers, and I have ties to communities like White Earth, where many people have shown support for my work. I did not really begin to publish until I had already left my hometown, so the opportunity to build those kind of connections came in other places. I have had the opportunity to publish writers from home though in anthologies I’ve edited and that has been fulfilling.

WV: Who are your favorite Wisconsin or Midwestern authors? Which Midwestern poets do you teach?

KB: Many of the poets I’ve named earlier are Midwestern writers. Other Native writers from the Midwest whose work I admire and teach include Heid Erdrich, Mark Turcotte, Jim Barnes, and Denise Sweet. Denise was one of our past Wisconsin poet laureates. Two other past Wisconsin poet laureates whose work I admire are Ellen Kort and Marilyn Taylor. I love the work of several of my poet colleagues at Milwaukee: Brenda Cárdenas, Rebecca Dunham, Maurice Kilwein Guevara and Susan Firer. I have taught Bill Holm, Sandra Cisneros, Pam Gemin, Kate Sontag, David Graham, Heather Sellers, Diane Glancy, Robert Bly, Ted Kooser, Lucien Stryk, Sonja Gernes, William Stafford, and—aren’t we rich with wonderful writers—many others. One class I teach includes variations on poetry of place, so I enjoy being able to introduce students to writers they might bump into in a coffee shop someday.

WV: What poetry or other writing projects are you working on right now?

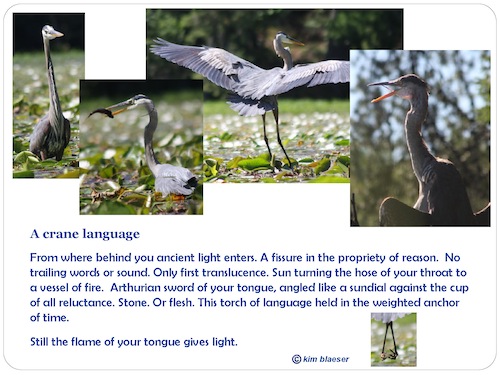

KB: I am just beginning a sabbatical year and have my head full of possibilities. For one, I plan a mixed genre collection of my creative work arising out of my long preoccupation with nature, Native place, preservation, and spiritual sustenance. The volume will include poetry, creative non-fiction, photographs, and collage. The working title, The Flame of Your Tongue Gives Light, comes from an image I took of a great blue heron in which the bird is backlit by the sun and panting with its long pointed tongue clearly visible: “Sun turning the hose of your throat to a vessel of fire.” The title and the longer poem allude to the astonishing moment of encounter with this creature and suggest that these earth moments provide spiritual light. The collection builds from similar transformational experiences a poetic sensibility about nature and place, but attempts to reconcile these beliefs with the practical challenges to such elemental attachments. Especially in addressing the ecological challenges, I draw on my travels to Indonesia, Taiwan, and Bahrain. Some of the work is done, some is still to be written. I am thrilled to finally have something beside snatched moments to work on a writing project. One segment of this work I am particularly excited about are pieces focusing on refraction.

At the same time I am working on a collection of essays and I just received word a couple of weeks ago that my play The Museum at Red Earth will be performed as a dinner theatre at the Menominee Casino in December so I look forward to that. My twelve-year-old daughter Amber and I have been writing together as well and she has begun performing with me a bit. In general, I have more ideas than time—and of course, as a poet, more time than money.

Wendy Vardaman, author of Obstructed View (Fireweed Press 2009), is co-editor of Verse Wisconsin and Cowfeather Press. Visit wendyvardaman.com.