Book Review

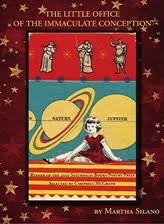

The Little Office of the Immaculate Conception by Martha Silano, Saturnalia Books, 2011. $14

Reviewed by David Graham

Contemporary American poetry, despite the regular appearance of articles bemoaning its mediocrity, sameness, and self-enclosure, is a tremendously variegated and vital field. Of course, all generalizations are false, perhaps more so now than ever. In fact, with literally thousands of new books and chapbooks appearing each year from all over the map, it's not only hard to generalize but very difficult even for a dedicated poetry reader (we do exist!) to keep up, to maintain anything like a clear sense of the immense terrain of American poetry. As a result of this historically peculiar abundance (or glut) of new poetry, it is also hard for any given book or poet to strike an unmistakably original or fresh note. Reviewers and blurb-writers are thus understandably prone to making their points with sweeping categorization, hyperbole, and oversimplification.

I step somewhat gingerly into this field, then, because I have been an unabashed fan of the poems of Martha Silano since I first encountered them about five years ago upon discovering Blue Positive, her second of three collections. One reason I wanted to write this review was to see if I could succeed in articulating why her work has struck me so forcefully. My expectations were high for her new book, The Little Office of the Immaculate Conception, but I am happy to report that the book did not disappoint.

At the risk of over generalization, I think it's safe to slot Silano's work firmly within a stylistic tendency that Alice Fulton once termed "maximalism." The primal parent here is clearly Whitman. Like Whitman's, Silano's are poems of large embrace and sweep, both linguistically and thematically. Of course, she is hardly alone in this stylistic tendency; she definitely shows affinities to a certain prominent strain of contemporary poetry. If one thinks of current poets Silano resembles, names like Albert Goldbarth, Lucia Perillo, David Kirby, Laura Kasischke, and Barbara Hamby spring most readily to mind: poets who often favor long lines, pell-mell syntax, wide mix of diction, eclectic subject matter, abundant humor, and an approach that is ultimately welcoming rather than opaque or veiled in layers of ironic detachment. Silano's poems in the new book, her best yet, demonstrate encyclopedic range and ambition, with a richness of language that can be dazzling. Consider this riff, which begins with a child having a "full-fledged conniption fit" about wanting something unnamed (a toy? stuffed animal? balloon?), but soon spins off into a sort of ars poetica, in which wanting becomes universal, with imagination or art the means by which we all yearn with childlike persistence:

... The one she's grown fond of, used to, the one to grow on,

grown on, drone on, which is what time it is, and what makes it

so special? And he says sparkles, but I say a story I can't quitefigure out. I say, we need a verb: to art! To take the ho hum mundane,

and sparkle-ize it. Catch my glittery drift? Mine glimmering eye.As in degree of usefulness. As in what the eye wants. Like billboards

salivating the dollar burger.

("In Praise of Not Getting")

And onward the poem rolls, rambunctious and unpredictable, with stops at a ball of yarn that a "guy's / been twining since 1967," a musical chord that "any Hindu, hay-seed, or Yoruba can grok (grok that?)," and "Neptune's 900-mile-an-hour winds," among other destinations-of-mind, always in language that glitters and prances. (One thinks here of Albert Goldbarth, of course, who quite fittingly titled his selected poems The Kitchen Sink, as in "everything but. . . .") The risks of such a sparkle-ized, maximalist style seem clear enough. At times a kitchen sink inclusiveness can seem forced or, worse, simply tedious—as it does, say, in some of Whitman's or Ginsberg's least inspired moments. Over time it can also be difficult to tell one poem from another: when free-ranging association is the main organizational principle, when poems at any given moment can swerve anywhere, they can all start to seem not only similar but arbitrary. At some point a poet's playful, dogged sprawl can become a reader's ordeal, may even risk turning into flat, uninspired prose.

Happily, Silano knows a few good tricks to avoid these pitfalls, one of which has just been illustrated: her often luscious and charged language. Another is to give her book some strongly unifying themes amid all the jump-cuts and turns, her skittery appetite for more more more. Even in the most freewheeling of poems there is typically a firm grounding of scene or idea. For instance, "I Live On Milk Street" is a sort of origin tale, a frisky meditation on humanity's place within the cosmic order ("Via Lactea" being the original Latin term for what we call The Milky Way):

Some say

it was born of Juno's wrath, wrath that toreher breast from a suckling infant Hercules

(her no-good hubby once again knocking upa mortal). What spurted up, they tell me,

begat this little avenue, this broad and ample roadwhere I merry-go-round with my 200-300

billion neighbors, give or take a billion or two.(Then again, it might've all been cooked up

by Raven.)

Similarly, "Santiago Says" a character piece, reports the unforgettable personality of a periodontist distracting his patient with sharp-edged banter and anecdotes:

My dad? He worked, you know,

in commercial wiring. So, this one time he goes touch that and I'm likeis it hot? And he's all of course not, no, no, go ahead. So I touch it

and it knocks me out. Know what he says? Don't trust nobody.

Again and again Silano's poems describe the most earthy, domesticated realities—a spat with one's spouse ("who forgot to pack the sunscreen"), wiping off a baby's snotty nose, garbage bags at the curb—against the largest imaginable backdrop of cosmic and geological infinities, scientific theories and technologies. Her poems are like those optical illusions in which the eye sees first a cat or woman's face, then a mountain range or constellation, and finally recognizes them as both-in-one. As Campbell McGrath, who selected this book as winner of the 2010 Saturnalia Books Poetry Prize comments, she is "comic and wise, quotidian and celestial," addressing "cosmology and motherhood in equal measure, because, after all, 'all of us were cooked in the gleaming Viking range/ of the stars.'"

It is perhaps in her unflinching but good humored explorations of the joys and tribulations of motherhood and family life that Silano makes her most distinct mark. Unlike some poets engaged in exploring the domestic and particularly female experience as poetic subjects, Silano is rarely just personal. Nor is she primarily political. She is, as noted above, both-in-one, the domestic always the lens through which the largest matters are viewed. "Our world is an oven; we are the temperature," she writes quite wonderfully in "Ours," one of a number of poems cataloging in Whitman-like extravagance this world's many tastes and textures. Poems such as "This Parenting Thing," "That Spring a Room Appeared," "This is Not a Lullaby," and "Poor Banished Children of Eve" are striking additions to the recent proliferation of poetry by women that delves into the psychic and intellectual complexities of modern family life, gender relations, and motherhood.

Maximalist poetry is hard to excerpt, for obvious reasons. But here are some lines that open "Poor Banished Children of Eve" that do demonstrate Silano at full-tilt, and give at least a taste of what she can do in a more extended passage:

I believe in the dish in the sink

not bickering about the dish in the sink

though I believe the creatorof the mess in the living room

cleans up the mess in the living room

sucks up cracker pizza potpie peanut popcornand I believe in the earth which also ends up on the rug

which must also be vacuumed up as I acknowledge

our blessings running water not teeming with toxinsand even though this might sound like nagging

especially in the face of dying and of burial

and of purgatory and of hell especially whenI could be instead of asking could you please

wipe up the olive juice that little pile of parsley

wailing and moaning at your wakeor maybe just sitting there stunned where beside me

sitteth the six year old and the 19 month old who most definitely

wouldn’t get the dying concept though maybe the sonfrom thence being the owner of two dozen dead ladybugs . . . .

Other poems may better illustrate Silano's more "cosmic" side, but read the above passage aloud and I bet you will be impressed with the jazzy sparkle of language and the emotional clarity of her perspective. This is a wonderful and highly recommended collection.

David Graham has taught writing and literature at Ripon College in Ripon WI since 1987. He is the author of six collections of poems, most recently Stutter Monk(Flume Press), and an essay anthology co-edited with Kate Sontag: After Confession: Poetry as Autobiography (Graywolf Press).