Book Review

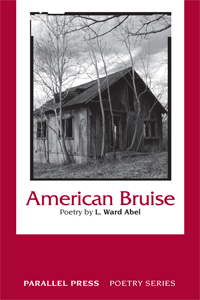

L. Ward Abel, American Bruise, Parallel Press, 2012

by Judy Barisonzi

It’s almost a truism to say that reading a book of poems is like embarking on a journey. If you’re lucky, it will be a journey to a special place, and you’ll see that place in a unforgettable way, through language that describes both an outer and an inner landscape. That’s the case with American Bruise by L. Ward Abel (Parallel Press, 2012). The place is small town, red earth Georgia. The time is the present looking back into the past, and the theme is loss. Each town has “a beautiful reverence for something lost” even if it’s only a shuttered fast-food joint:

As if the

Hardee’s hamburger place could ever

come back from the dead out here. (“Towns Like Greenville”)

The theme of loss is set in the very first poem, “Leaves,” a poem about Walt Whitman, with the obvious allusion to Leaves of Grass, but the title is also a play on words. What is left? is Abel’s question, and his answer is that something is left, though he’s not sure what:

Things were made to remain,

but not people, maybe not even words.

What’s left might be memory, memory of all the little things that made up a way of life. “[R]emember this for me,” Abel’s father, memory fading, says to him as they drive around the small towns and countryside. His memories are mostly small, maybe insignificant—“a line where sand turns/to clay” or where “Charlie Brown and his/beautiful daughters lived,” but he remembers also the place where they dug up ancient shark teeth, a connection to a deeper past. To the old man, all these memories are “[j]ust wonderful” (“Lizella”).

It’s language that creates wonder. For example, Abel describes the red clay earth as “rusted wine” (“Red Clay”), a phrase carrying implications of something old, destroyed, yet sacred. “Decay,” he writes, “is/the very essence of complete sacrifice” ("Something Good Has Come From Rotting").

Abel himself, in these poems, rarely sees the wonder of existence. He has lost his job (see “Walk”) and pictures himself as “an oak leaf spinning across winter grass/tethered to smoke” (“Walk”). Yet he is not entirely unconnected to his past or without succor: “I think I have some moments still in my pocket but the way/overgrows” (“Walk”). Or:

Out over the pond

I’m suspended. The summer night

is void of air but I breathe in

handfuls of life. There’s

no rope but God’s rope looped around

me. (“Water and Night”)

Untethered but still dimly connected, lost but not past hope--these are themes that Abel, through numerous metaphors, reiterates throughout the book. Recurrent images are roofs and portals, doors and tunnels:

the light the tunnel are one.

We just perceive

moving towards something, never

reach it, because it’s the starting point.

We have the sensation of movement

to where clear water springs up and is

named river, to where it’s too high for

rarefied climbers,

to corners where our shadows

can finally recline, to better hours,

to a closure. (“Tunnel”).

Occasionally Abel draws specific pictures:

it was my own name I heard

in the voice of my mother

when she was young. I had

a crew cut, a small red coat. (“Names”)

And he has moments of insight, of vision—of a woman singing, “like rainwater spilling” (“Dithyramb”); of birds—

when he [a crow] cut over

the tall grass it parted

as if a little Moses

told it to part (“Red Crow”);

of mountains—

The old mountain knows that he’s left me

unfinished on the nightstand again. (“Walk”)

Death is a constant theme, but “death isn’t the word I’m looking for” (“Leaves”). It’s far from final; Abel writes

nothing really dies. But no one

relishes the door. (“Portal Fear”)

or, with an infrequent flash of humor:

I’ll bet

his casket had an escape hatch (“Miles Refused to Die”).

American Bruise begins with evocation of a lost place and ends its journey with an affirmation of finding one’s place, of survival, of living in the moment:

On mornings

I wake

into thought, cross the stream

over stones. Waters

divide things like night and day.

I enter another template. Here

I make my life. (“And Long Live That Dream”)

That’s the final assertion in the book, and it seems a bit forced to me. Abel says it better through metaphor, whether it’s a flock of blackbirds on the lawn—

They weren’t there just a

moment ago.

. . . My eyes

capture the weight

of a thousand wings. I look away

and we are gone. (“We”)

or the patchwork of farmers’ fields—

Great wide clearings they seem flat they

seem like rectangles fitted, reclined,

one’s west wall is another’s eastern

fenced by a boundary of flesh. (“Geometry”)

or a rusted, discarded washing machine

The bather in the holy Ganges

has it right, that this moment

is all there

has ever been. (“Appliance, in the River”)

Judy Barisonzi has been a Wisconsin resident since 1966, and she now lives among the lakes and woods of northwest Wisconsin. Semi-retired from teaching English at the University of Wisconsin Colleges, she gives workshops in creative writing and memoir writing, participates in several local writing groups, and publishes poems in local and national magazines.