Interview with John Koethe

By Wendy Vardaman

Chester by John Koethe, Produced by Poetry Everywhere

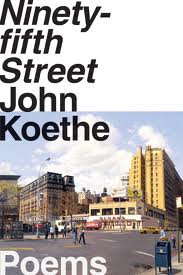

WV: Place seems to figure more and more prominently in your work. In Ninety-fifth Street it is everywhere—the California of your childhood, New York City, Boston where you went to grad school, Milwaukee, Europe. How do you use place? For its own sake? Metaphorically?

JK: In several ways. First, I have a natural tendency to write abstractly, and tying a poem to an actual place helps counterbalance this a bit. And second, one of the pervasive themes of my work is the romantic opposition between the individual subjective consciousness and its external objective setting in the world, which is what all those places represent. Beyond this, Ninety-fifth Street is really a book about cities. In addition to the ones you mention, there are also Berlin, Venice, Cincinnati and Lagos.

WV: Has your use of place changed over time? It seems to me, for instance, that a poem like “The Late Wisconsin Spring” feels much more like a traditional, even Wordsworthian lyric, whereas the more recent poem, “The Menomonee Valley” is looser, more conversational, more pessimistic—it’s about collapse, rather than expansion. Is that a trend in your work, or just the difference between two poems?

JK: I don’t think of my work as pessimistic, but rather as disillusioned. I think we’re drawn to romantic illusions even though we know perfectly well they’re illusory. I think “The Late Wisconsin Spring,” as well as “In the Park” from the same book, indulge those lyric illusions a bit more than much of my later work, though ultimately those poems undercut them too.

WV: What role has Wisconsin played in your poetry? And I don’t mean metaphorically. Do you feel it’s been a disadvantage poetically to live in the Midwest, as opposed to New York City, where the title poem of your new book is set?

JK: It’s sort of a tradeoff. On the one hand you forego a lot of the networking and career opportunities of living, say, in New York (I was quite conscious of this when I spent last semester at Princeton). On the other hand, I intensely dislike schools of poetry and thinking of poetry as a job or career you’re pursuing, and the relative isolation of living in Milwaukee, which I like very much, helps protect me from this.

WV: You spent a semester at Princeton on a visiting professorship in poetry. How would you compare teaching poetry writing to teaching philosophy?

JK: At Princeton I didn’t teach poetry writing, but rather gave a seminar in the English department on the New York School. My entire experience teaching writing consists of serving as the Elliston Poet in Residence at the University of Cincinnati in 2008, teaching a course on the long poem at Northwestern in 1990, and doing an independent study in the 1970s that produced my one poetry student, Henri Cole. I sort of enjoy teaching poetry writing now and then, but wouldn’t have wanted to dedicate my life to it. For one thing, I think you have an obligation to help your students develop in their own direction, even if you don’t particularly care for what they’re trying to do. Making my living teaching philosophy allows me the luxury of my dislikes, so to speak. Also, philosophy has a clarity and integrity from which I think my own poetry benefits.

WV: There’s been an increased professionalization of poetry these last 20-30 years through MFA programs. Do you think the university is the best place for a poet to be? Does it matter how poets earn their living?

JK: Well, I’d want to distinguish between universities and MFA programs. I think universities are wonderful places for poets to be—after all, that’s where most of their readers are. On the other hand, I just indicated that I’m uneasy about the professionalization and commodification of poetry through writing programs. I think it’s desirable to have other intellectual interests as well.

WV: I read that you only write poems during the spring and summer? Is that still true? Why do it that way?

JK: While I was teaching I’d work on philosophical writing in the fall and winter, and then shift to poetry sometime in the spring. I have a feeling that lying fallow half a year made my poetry feel fresh when I returned to it.

WV: The sense of time in your work is unhurried, not frenetic, very different from many contemporary poets. The pacing of many of the poems underscores that, too, and they often unfold in a leisurely way, reading as though they were composed slowly and with great care. How long do you typically write at the first draft of a poem? How much time do you spend revising work?

JK: I think your observation about the pace of my work is quite accurate. I write slowly, in small bits, in the morning, with lots of revising and then more revising in the evening. Then the same thing the next day until the poem is finished. I rarely complete a full draft of a poem, but rather build it up by accretion. I usually have a sort of architecture in mind for the poem, but not too much of its contents. It’s exciting to me to fill it in, to discover, as it were, what the poem is about. This was especially true of a long poem I wrote in the 1980s, “The Constructor,” in which I started with the last line and then worked backwards to the beginning.

WV: Do your poems ever involve research?

JK: No, not that I can think of.

WV: You retired in January, 2010 from the Philosophy Dept. at UW-Milwaukee—congratulations. What are your plans for retirement, and how might more time affect your writing? Will you stay in Milwaukee?

JK: Well, I plan to continue working on poetry, and also making use of a house I just built in southwest Wisconsin in the driftless region (it’s the house I was imagining at the end of “Ninety-fifth Street”). I do plan to stay in Milwaukee, a city of which I’m very fond. I toyed with moving to New York for a bit, but it’s too expensive—who wants to retire and go back to living like a graduate student? Better to live in Milwaukee and go to New York a lot.

WV: What writing or poetry projects are you working on now?

JK: Well, I wrote a fair amount at Princeton, and since I’ve been back I’ve been preoccupied with reorganizing my apartment to accommodate the stuff from my office at UWM and with the arrangements for my son’s wedding, which was last week. I just started tinkering with a poem called “ROTC Kills,” a sort of memory poem that takes off from an old poster from the 1969 student strike at Harvard that I have on a wall in my house in the country.

WV: I want to know more about your dual life as a philosopher and a poet. Poets who know your work know you are a philosopher, but do philosophers know you’re a poet? How do they respond to that?

JK: I think a fair number of philosophers know I’m a poet—there are really only one or two other philosopher poets that I know of. My colleagues in the philosophy department were very accommodating and generous in recognizing and allowing me to pursue my poetry. Of course, I kept up my end of the bargain by writing a reasonable amount of philosophy too.

WV: Philosophy is a major source of themes, of ideas in your poems. Has it affected your poetry in other ways?

JK: I think the abstract, discursive rhetoric of philosophy has influenced the way I write poetry. I know that lots of people associated with poetry hate that kind of language and think poets should avoid it, but I think it opens up all sorts of possibilities it’s foolish to ignore. You can see this sort of rhetorical influence in T.S. Eliot’s work, especially in “Four Quartets,” a poem a lot of the “no ideas but in things” people loathe. It’s no accident that Eliot was trained as a philosopher—unlike Wallace Stevens, say, another philosophical sounding poet who never seems quite as at home with the idiom as Eliot. There’s a popular stereotype of philosophical writing as murky and unintelligible, but actually just the opposite is true of good philosophical writing.

WV: Does poetry impinge on your philosophical writing? Are there areas of overlap in the writing of philosophers and poets in general, or do you find the two types of writing very different?

JK: Well, I suppose the current paradigmatic philosophical writing style is extremely detailed, rigorous and explicit, with few broad strokes. My own philosophical style is somewhat looser and more essayistic, though whether this reflects the influence of poetry I’m not sure. It probably just reflects a preference for the essay over the academic paper.

WV: Have you felt equally successful in these two fields and equally engaged?

JK: I think I’m better known as a poet than as a philosopher, and probably have a deeper attachment to poetry. But I wouldn’t want to exaggerate the difference—I have a great love of philosophy, and I’m a respectable philosopher, though I’m not a luminary.

WV: Why do you write poetry rather than just philosophy? (or vice-versa?)

JK: I’ve always loved literature and something else. In high school it was modernist fiction plus math and physics. Then it was poetry plus philosophy. I just wanted to pursue both.

WV: In “Moore’s Paradox,” North Point North you write, perhaps ironically or facetiously, about a dislike of poems about philosophy, and yet your poems are always about major philosophical problems: identity, memory, belief, God, time, perception, the mind, epistemology…though not, it seems to me, ethics. Are the beliefs in your poems your beliefs, or do they belong to a persona?

JK: You’re right—ethics isn’t much reflected either in my poetry or in my professional philosophical work. What I meant by that somewhat facetious line is that I don’t like poems that present themselves as vehicles for conveying or doing philosophy, as some (though not all) language poems do. The themes you mention are ones I think philosophy and poetry share at some deep level, but they approach and develop them very differently. Philosophy is subject to severe constraints of consistency, coherence, argumentative rigor, addressing of objections and so on, with the aim of arriving at the truth of the matter. Poetry isn’t subject to these constraints, but is free to inhabit and explore ideas and themes without worrying too much about their correctness, as long as they feel sufficiently powerful to move us. Another way to put it is that I try to put myself, through an act of the imagination, in the position of someone who does believe them, and to discover what that’s like. I tried to spell this out in a recent essay called “Poetry and Truth.” So I’m not sure you could call them beliefs, but whatever they are they don’t belong to a persona.

John Koethe reads "ROTC Kills" at the Verse Wisconsin Reading, Avol's Bookstore,

WI Book Festival, 9/30/10, video by Robert Wake.

WV: At the end of the poem “Ninety-fifth Street,” you talk about “two versions of myself/And of the people that we knew, each one an other/To the other, yet both indelibly there: the twit of twenty/And the aging child of sixty-two, still separate.” So there’s that question of whether we are the same person over the course of a lifetime and in what sense, and although you simplify it here to a dualism, twenty or sixty-two, those lines imply a calculus of endless other selves spilling across time. Philosophically speaking, where, if anywhere, do you locate identity? is that different when you think poetically?

JK: It’s a question that obsesses me, but to which I don’t know the answer. At one extreme the self is a real thing existing throughout a person’s lifetime (or afterlifetime if there were such a thing). At the other it’s fleeting and momentary, or not even real at all. The first is probably a deep and inescapable illusion, while something like the latter is probably true but unbelievable. I sort of oscillate between them in my poetry, taking them up and inhabiting them as I described earlier.

WV: Writing about the “regret/And disappointment” that hangs over your poetic landscape, you say “The happy and unhappy man inhabit different worlds,/One still would want to know which world this is,” which reminds me somehow of William James’ essay, “The Will to Believe.” Do we have the capacity to choose which world to occupy? To exercise belief rather than doubt?

JK: “The happy and unhappy man inhabit different worlds” is a quotation from Wittgenstein’s Tractatus which has always puzzled me. He can’t mean it literally, given what he means by “world.” In any case, I don’t think belief can be voluntary. I think we’re often drawn to believe things we know at a higher level to be false. My favorite example of this is philosophical dualism, the idea that the mind or self is something real and distinct from the physical body. I think it’s deeply embedded in our self-experience, even though we know it can’t be true.

WV: You write about the profound effect on you of the play Hamlet in your poem by that title in Sally’s Hair. Did going to see Hamlet really change your life? Can you imagine your own poems having that kind of effect on a young person, perhaps even through misreading? How would you feel about that?

JK: The idea that seeing Richard Burton’s Hamlet in 1964 changed my life was just a mildly amusing conceit I was toying with in that poem. It isn’t true of course, but the fact is that something shifted around that time, and since I don’t really know what it was I just though I’d blame it on Burton. As for my own poems affecting someone in a drastic way, I guess it would be fine as long as it wasn’t for the worse. I suppose like most poets I get letters now and then to that effect, but I never know what to make of them.

WV: I’d also like to ask about the intersection of science and poetry, math and poetry. There isn’t a lot of work done on these borders, but it seems that it’s becoming more interesting to poets—or perhaps poetry is become more interesting to scientists. You originally planned to study physics at college. Have you maintained an interest in science and math? Would you like to do more with them in your poems?

JK: I’ve maintained an interest in them, but I wish I’d continued to study them, since philosophy of mathematics and philosophy of physics interest me very much, but I don’t know enough mathematics and physics to pursue them seriously. As for poems, there are some glancing references to scientific and mathematical themes throughout my poems, and I did write a short poem called “Strangeness” which had a bit to do with a phenomenon called quantum foam.

WV: Are there any poets you would point to, currently or from the past, who put their scientific/mathematical minds to use, and does that manifest itself more as an interest in facts from those fields, in their concepts, in the material world itself, or in the metaphorical uses of various facts and theories?

JK: Lucretius aside, not much comes to mind, though Douglas Crase, George Bradley, Richard Kenny and James Richardson, all poets I admire a great deal, have keen scientific interests. Emily Grosholz, one of the few other philosopher poets, works on the history of science and mathematics, but that hasn’t been reflected in the poems I know of hers.

WV: In the interview you did of John Ashbery (1983), you asked him about the changed poetry landscape from the 50s to the present—I’d like to ask you the same question. How has the poetry world changed since you began publishing in the 60s to now?

JK: Well, the most obvious change has been the explosion of writing programs and the resultant great increase in the number of poets and books. While there are many very strong poets writing, I keep thinking that poetry is becoming more of a craft like ceramics, something you can just take up and learn if it appeals to you (which isn’t to say that there aren’t great ceramicists). One result of this proliferation is that there’s not much consensus on who the important poets are now. Another change that strikes me is in the kind of ambitions poets have. When I was teaching the seminar on the New York School at Princeton last semester I was struck by how the original members of that school (which really wasn’t a school) aspired to and attained, I believe, a kind of greatness and a transcending of their influences, whereas the New York poets that followed them didn’t seem to have that sort of ambition (I’d make an exception for Douglas Crase).

WV: Could you comment on the nature of Ashbery’s influence on the current poetic landscape and on your work specifically? Where would you say you part company, poetically speaking?

JK: Ashbery’s work divides into a number of phases, consisting roughly of the books before and after Flow Chart. His work in the second phase, while still quite wonderful, is more aesthetic than meditative and quite influential on a sort of generic poem a lot of younger poets seem to be writing. The most important phase of his work for me is the period from Rivers and Mountains through A Wave, in which he wrote some of the greatest meditative American poems of the twentieth century. I think his main influence on me was stylistic—the long, supple sentences with lots of clauses and qualifications, the meandering way a poem can progress, the sense of an abstract and indefinite landscape or atmosphere. A main difference is that Ashbery is more interested in creating the sensation of thought, whereas I’m willing to go along with some actual thought (which I’m not saying is a virtue).

WV: One of the last images in Ninety-fifth Street is of Ashbery “whenever I look up I think I see him/Floating in the sky like the Cheshire Cat,” (79) a grin, perhaps, without the cat. You begin the book with a poem about Chester, a cat who very definitely does not have a smile, and I’m wondering—a round about way to ask you about your own sense of humor—which image you’d prefer someone to associate with you? Do you think of your poetry as humorous?

JK: I’m certainly not a comic poet, but I do think there’s quite a bit of subdued humor in my poems—reflected in a certain casual, throw-away manner, for instance. The critic and poet James Longenbach told me that when he teaches my work to his students at Rochester, he tells them that the humor in a Koethe poem is like the vermouth in a dry martini, which seems pretty accurate to me.

WV: Besides modernist poets like Eliot and Stevens and then Ashbery, or a novelist like Proust, what writers, artists, or philosophers have influenced your poetry? Do you have new influences as you get older, or is that more part of being a young writer?

JK: I think most of your formative influences are encountered when you’re young, though I did find myself responding to Phillip Larkin as I got older. Besides the writers you mentioned, I’d include Elizabeth Bishop, James Schuyler, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Pynchon, F.T. Prince and Kenneth Koch in his late elegiac mode. I’m sure there are others, but those come to mind. And Ludwig Wittgenstein has certainly influenced me both intellectually and stylistically.

WV: Are there any contemporary poets you particularly enjoy reading?

JK: Quite a few, including Frank Bidart, Henri Cole, Douglas Crase, Mark Strand and Susan Stewart.

WV: Poetry has many partners these days, and although these relationships have existed in some cases for a very long time, it is now possible, because of the nature of the internet and powerful software, to bring them together in one online journal, sometimes within one single work. I’m thinking of visual poetry, poetry animation, audio and Spoken Word performance.What do you think about the nature of poetry under these influences and given the possibilities? Will it change, or is there something fundamental about it that will prove unalterable? Do any of these possibilities interest you?

JK: I have to confess that these sorts of resources don’t interest me. I’ve often described poetry as an artful form of talking to yourself, and if that’s right then it will be around as long as people are drawn to do that, which is to say as long as they’re self-conscious.

WV: You’ve spoken previously about the fact that you don’t write for an audience. Was that a conscious choice on your part, or something you drifted toward naturally? What do you think about poetry that is consciously written for a reader?

JK: I think I’ve always thought of poetry as a kind of inner soliloquy, reflecting the capacity for self-consciousness that makes us human. But I wouldn’t want to be essentialistic about poetry. If someone thinks about an audience and writes poems directed at it, that’s fine, though such poems aren’t likely to lodge themselves in my mind.

WV: Rachel Hadas, in a review of Falling Water (1997), said in praise of your poetry: At a time when so much poetry stands on a soapbox and orates or lies on a couch and weeps, or else breathlessly buttonholes the hapless browser, these poets (it sounds so modest) speak. That is, they do not weep or scream. Others take your work as gloomy, acutely aware of failure and futility. How do you see it?

JK: Well, I certainly don’t see it as gloomy (nor do I see it as mourning a lost childhood, as Charles Simic suggested in a recent review of Ninety-fifth

Street). I earlier described it as disillusioned, by which I meant that I want to avoid and deflate facile consolations and celebrations. A lot of our impulses and aspirations are futile (and a lot of them aren’t)—that isn’t gloomy, that’s just life.

WV: It seems to me there’s an amazing unity of voice and aesthetics, along with control, in the body of your work. I’d note that besides a set of philosophical themes and a unifying narrator, there’s also, among other characteristics, an abundance of references to modernist writers and an almost total absence of pop culture references, in contrast to the work of many (maybe even most) contemporary poets, including Ashbery. Is that deliberate, or is it something that just doesn’t interest you?

JK: I actually think there are a lot of pop culture references, though certainly not as many as in someone like Ashbery. Just off the top of my head, I can think of references to Lou Reed, the Velvet Underground, Peggy Lee, Mark Knopfler, numerous movies, the novels of Raymond Chadler and the Drifters. Now Wallace Stevens—there’s someone whose work is devoid of any reference to popular culture.

WV: There’s a particular narrative strategy in many of your poems—the distance/absence of a personal narrator or of feeling, or the movement between the impersonal and the first person, in e.g., “Home” or “Belmont Park.” Thus the beginning of “Home”: “It was a real place: There was a lawn to mow/And boxes in the garage. It was always summer/Or school, and even after oh so many years/It was always there, like the voice on the telephone.” Your use of “it” and “there was” here is quite striking, especially as that choice creates tension with the expectations that a title like “Home” sets up. Could you comment on this strategy?

JK: I do try to oscillate between a subjective first-person perspective and an impersonal, sub specie aeternitatis perspective. I think of this as a vestige of the movement of thought Kant called the sublime, one that lies at the heart of romanticism.

WV: I’m wondering about the fact that you don’t write poems about the experience of being a father—is that a deliberate choice?

JK: I guess my poetry isn’t terribly interpersonal, but I can think of passing references to fatherhood in “Falling Water” and “Ninety-fifth Street” (though not really about the experience of it).

WV: Have you ever written a deliberately fictional poem? And by that I don’t mean simply a persona poem whose narrator is not the author. I mean a poem that constructs a fictional character who inhabits a fictional world. I’m also wondering if you’ve ever written a narrative poem about a historical person.

JK: Not about a historical person, but the second section of “Mistral” in The Constructor imagines and describes a fictional character. It was inspired by a photograph of James Merrill wearing an elegant shirt on the cover of a book of his selected poems.

WV: Your voice has a characteristic minimalism when it comes to rhetorical device, rhyme, sound play. It seems very pure and mostly devoid of ornament, sculptural almost. Is that a fair characterization?

JK: I think so, though there’s quite a bit of assonance and internal rhyme and half-rhyme I rely on to hold things together. But I do try to avoid highly charged rhetoric and figurative, poetic language, and usually look for a lower-keyed alternative.

WV: You also sometimes speak about your writing using architectural metaphors—building and blocks for instance—could you comment on your approach to writing, how you go about the process of assembling a poem?

JK: I usually start with an idea of the poem’s architecture, by which I mean an abstract image of what it’s going to look and feel like—length, stanza structure or lack of it, longer or shorter lines, the kinds of rhythms and cadences involved, emotional intensity, density of language, formal or colloquial diction, in fact almost everything but the content, though I’ll usually have at least a vague idea of that too. Then I start to fill it in, usually at the beginning of the poem, though not always. I’m heavily dependent on the shower and shaving, when I get my ideas for anywhere from one to about ten lines, which I’ll then write up and work on. I look at them again before and after dinner, and fiddle with them some more, and then repeat the process each day until the poem is done. Then I’ll keep going over it until I’m satisfied with it.

WV: Your poems are written sometimes in free verse, but they are often quietly metered, or in syllabics. “The Distinguished Thing” in Ninety-fifth Street goes back and forth between prose and verse. There’s occasional, but generally not regular, rhyme, which reminds me of Eliot’s practice. How do you decide to use rhyme on the occasions that you do? Does the idea of working with traditional forms, such as the sonnet, interest you? what about prose poems?

JK: Sometimes I’ll just feel like writing a poem in rhyme, like “What the Stars Meant” in The Constructor, a poem I’m quite fond of. Or sometimes a variable rhyme scheme is a way of holding a long poem written in sections together, as in “The Secret Amplitude” in Falling Water and “The Unlasting” in Sally’s

Hair. Traditional forms like sonnets don’t appeal to me much, though I do write short, sonnet-like poems. Often when I write in forms, they’re of my own devising. As for prose poems, I usually don’t care for them because of their soft surrealist connotations. But as you noted, I did use prose in “The Distinguished Thing,” and I recently wrote a poem in prose called “Like Gods,” which is probably the only explicitly philosophical poem I’ve ever written. But it might be better to call it a poetic essay than a prose poem.

WV: I’d also be interested in knowing how you came to the use of syllabics, which is something I’m doing a bit of research on right now.

JK: I sometimes use syllabics to counteract my tendency to slide into a natural iambic rhythm. But I’ve also written in the kind of regular stanzaic structures with lines of varying numbers of syllables that Marianne Moore uses—it gives you something that feels like both poetry and prose. The first section of the title poem in Domes is written in that kind of form, though I haven’t done that for a long time.

WV: Is there anything in particular you would like readers to notice about you poetry that they generally don’t?

JK: Well, I know my work has a reputation for being somewhat cerebral, and while I suppose it can be, I think the most important thing about it is its emotional intensity. Eliot said somewhere that what is sometimes regarded as a capacity for abstract thought in a poet is actually a capacity for abstract feeling. I’m not entirely sure what he had in mind, but I think it applies to my own work.

Wendy Vardaman, author of Obstructed View (Fireweed Press 2009), is a co-editor of Verse Wisconsin. A review-essay that includes Ninety-fifth Street can also be found in this issue. Visit wendyvardaman.com.