Beyond Ekphrasis: Collaboration as a Journey

By Sara Parrell

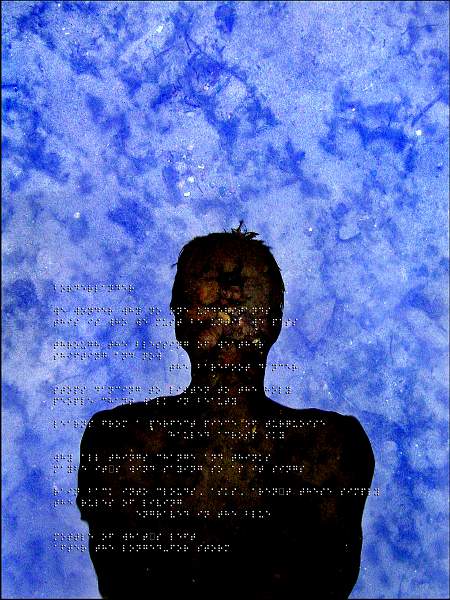

Borderlander, by Sara Parrell

Sometimes it’s as easy as driving down a street you haven’t cruised for over a year, a street you love because it skirts the blue of Lake Monona, and you are paying attention as if it was the first time. You slow down as you near the house of an old friend, and glimpse him in the bricked back yard, working on a new piece. And although you are already late for a gathering across the Yahara, you ease to the curb, slide it into park, and walk down his driveway to say hello. “I was thinking of you recently.” Fifteen minutes later, it’s in motion. His photographic portraits, the poetry you and your fellow poet friends will write in response to his work, and the art that is born from this.

What Holds Us, by Alison Townsend

Collaboration between poets and artists, and poets and photographers in particular, is not a novel idea. In the 1950s and 60s at the New York School, painters and poets shared a social scene and a community, appearing frequently in each other's work and letters, reading together, working on literary journals, and becoming champions of each other’s poetry and artwork. On a recent exploration of the three-story Renaissance Book Shop in Milwaukee I discovered Adventures in Value printed in 1962, a collaboration between E.E. Cummings and his photographer wife, Marion Morehouse, a synthesis of the personal expressions of two artists. In 1967, Pablo Neruda invited social documentary photographer Milton Rogovin to Chile to collaborate on a project that resulted in the book Windows That Open Inward where Neruda honored the photographer’s desire to “photograph the truth” with his responsive poems. More recently, poet C.D. Wright and photographer Deborah Luster documented the experience of incarceration in the book and traveling exhibition One Big Self: Prisoners of Louisiana. As Wright offers, “collaboration is the buzz these days,” and there are growing examples of photographers and poets attempting to listen to each other deeply, search for their twin sensibilities, and in that process produce a work that is more than the sum of their efforts.

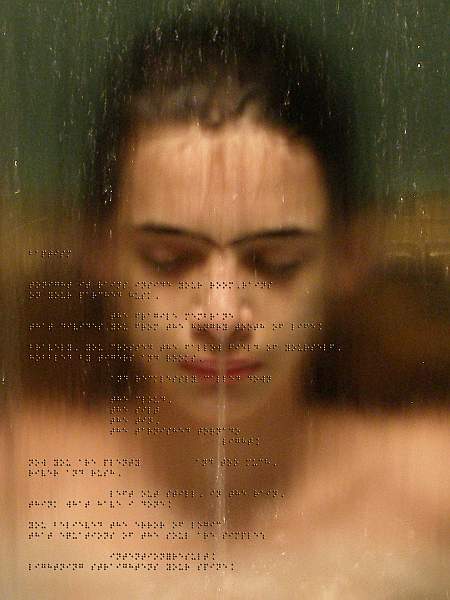

Baptism, by Susan Elbe

“Borderland” evolved from that spring-of-2009-patio-chat between two friends, photographer Thomas Ferrella and me. We had collaborated previously on a project, “Nocturne,” wedding his videography and ambient sound shapes with the works of three poets. Now he’d hatched the idea of pairing his unmanipulated digital photographic portraits with poetry for the annual fundraiser for the Wisconsin Council of the Blind and Visually Impaired, an organization located in his neighborhood. Poems written in response to his work would be brailled onto the print, blending his images, which already straddled the line between seeing and feeling, with touchable words. “I’m a sensualist at heart, so why not use touch as part of that? Why ignore touch?” I was eager to accept his invitation to be involved, and suggested that other poets in my writing group, Lake Effect, would likely be enthused about the concept and willing to participate. During that fifteen minute conversation, something akin to a chemical reaction was initiated, a physical sense of excitement, a tuning-into the synchrony and connection possible in this world.

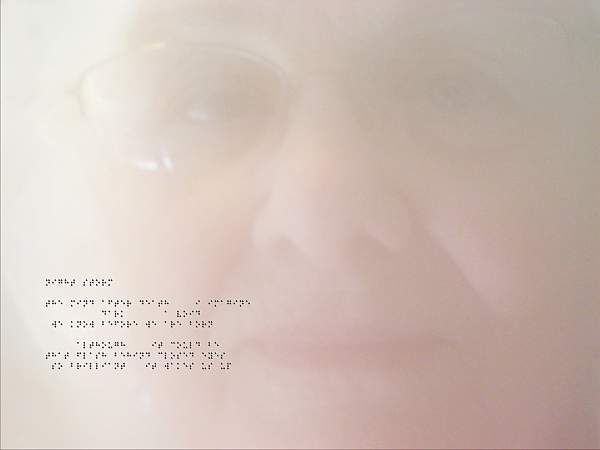

Between May and December of 2009, seven poets (myself, Robin Chapman, Susan Elbe, Rasma Haidri, Catherine Jagoe, Jesse Lee Kercheval and Alison Townsend) responded and interacted with the visual work. We elected to match one of Thomas’s images with a poem written by Judith Strasser, an originator of our group, who had died the previous January. In our view, the poem “Night Storm” from her unpublished manuscript Limited Warranty (www.judithstrasser.com), uncannily resonated with the photograph of Thomas’s mother’s face emerging from a fog:

the mind after death I imagine

dark a void

we know before we are born

although it could be

that flash behind closed eyes

so brilliant it wakes us up

Night Storm, by Judith Strasser (read by Robin Chapman)

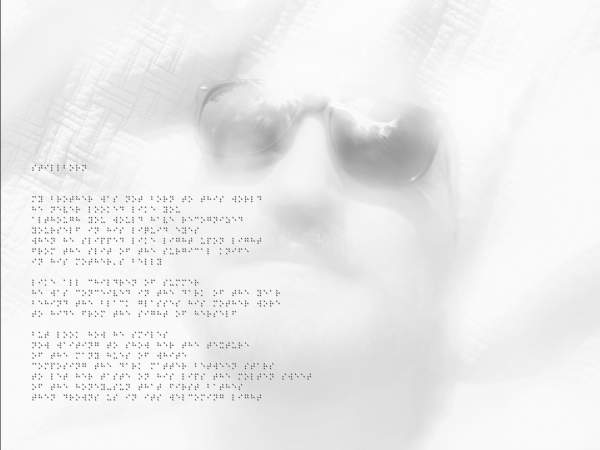

The process of collaboration between photographer and writer can take many forms, and for the remaining eight portraits, we agreed to match poet to portrait by tossing their tentative titles (the name of the person photographed) in a hat. After the draw, and a bit of bartering, we entered into the writing. Names were nudged out by poem titles, and Thomas was impressed with the fresh and often unexpected dimension these added to his work: Miranda transformed into “The Beginning of Fire,” Zachary into “Baptism,” Self into “Borderlander.” The search for a title for the entire show was taken on by all of us, and Thomas chose “Borderland” from our pool of suggestions, adding a subtitle commensurate with his initial impulse: “where worlds arise out of touch.”`

Stillborn, by Rasma Haidri

As the voice of the collective of poets, I communicated with Thomas often by email, phone, and a handful of person-to-person interactions. Our conversations ranged from the pragmatic (e.g., calculating limits on line length in order to braille the entire poem on the print without compromising the image) to the creative and philosophical. After the first poem was successfully brailled onto a print (a technical and artistic process that eventually enlisted the talent of WCOB member Virginia DeBlaey), Thomas brought it to one of our Lake Effect gatherings, meeting the other poets for the first time. The new form created from the physical melding of the word and the image animated us. Then, and over the course of the collaboration, we shared our curiosities and impressions: How were the dream-like portraits created without computer manipulation? What kind of camera? Why this line break, that stanza break? Why this word, and not that word? How could our poems enhance the process of “seeing” the portrait? What was the connection between touching the poem and experiencing the image? What could we (and perhaps others) learn through this project about the world of those who are visually impaired?

The Ice Does Not Melt, by Jesse Lee Kercheval

Unintentionally, as the poems took shape, they reflected each other as well as the photos, and the process of photography. Themes of the interplay of light and darkness, degrees of seeing, and seeing the self, emerged: “the honey-sun that first bathes/then drowns us in its welcoming light,” “here in the darkroom of mind/this is what happens to love,” “your face/that my fingers trace/is another Braille,” “engraved in the blue/mottle of what’s left/after the longed-for storm,” “she sets the world afire,” and “Lightning straightens your spine.” Not only had our co-creative process allowed us space to look inward, it had also resulted in a dynamic product, the impact of which was yet to be realized.

The Dark Room in Your Head, by Catherine Jagoe

In addition to the brailled prints and our oral reading of the poems at the first opening, Thomas and Kathi Koegle, WCOB staff member in charge of community outreach and development, made decisions to create and make available a book with photos and poems and a CD with the poems recorded by the poets. A multi-sensory approach seemed consistent with the project’s intent. Our assumptions about the meaning of blindness and visual impairment, about literacy, about story telling, about engagement in the community, began to bubble up. Interestingly, shortly after the show opened, a New York Times article by Rachel Aviv, “Listening to Braille,” was published. She points out that Braille, a modified version of the “night writing” used by French soldiers in the early 1800s to allow message-sending in the dark, is now used by less than 10% of the 1.3 million legally blind in America. Her discussion of the questions raised by the transition from Braille to computerized speech (somewhat parallel to the transition from print to digital text for the sighted) challenges the definition of what it means to be literate, puts the definition of “book” or “read” up for grabs. E. Ethelbert Miller, a Washington D.C. poet and writer, suggests via his blog that replacement of physical books by E-Books (the physical word by the digital word) could usher in a time where writers are more engaged in their communities: “Instead of autographing sessions there will be more conversations and dialogue with the public. Writers will cast aside the role of being entertainers and assist our communities with the task of heavy lifting. The new technology will usher in a new era of freedom and expression.” In my experience, the collaboration of artists and writers increases the potential to participate in the important, and sometimes critical, discussions necessary for adding value to our world.

The Beginning of Fire, by Alison Townsend

We see and hear what we are open to noticing. I had the fortune of noticing a friend and fellow creative spirit, working in his backyard on a warm spring evening with its perfect slant of light, its new-green breeze. I had the fortune of allowing his request to reverberate next to my own inclinations to create, to see from new perspectives, to involve the talents of my fellow writers. Wright says, “What’re an American photographer and poet to do? Well, go there, auscultate, poke around, come back and report, and put it on view.” “Borderland” is a view created over time by nine artists doing their honest best, with gratitude for the ride.

Kim With Her Eyes Closed, by Robin Chapman