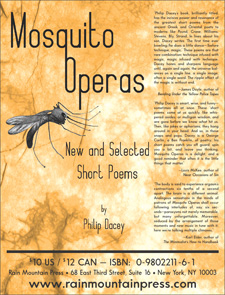

Philip Dacey, Mosquito Operas: New and Selected Short Poems, Rain Mountain Press, 2010. $10

Reviewed by Lisa Vihos

If mosquitoes could sing, their operas would be short, wouldn’t they? But they would be no less moving than their full-length counterparts for their brevity. Such is the case with a new collection by Philip Dacey, Mosquito Operas: New and Selected Short Poems, (Rain Mountain Press, 2010).

Like last year’s Vertebrae Rosaries: 50 Sonnets (Red Dragonfly Press, 2009), Mosquito Operas also gives us poems that span Dacey’s career, going as far back as 1970. Here again, we get to enjoy the poet’s characteristic dry humor, smoldering intimacies, and acute observation of daily life:

The Condom's Nightmare

I grow up

to be the Hindenburg.

The first section of the Operas contains several such one- to three-liners. The “BA-dum-dum,” that might accompany a stand-up comedian’s routine audibly punctuates Dacey’s quips as they buzz past your ear.

Thumb

The odd, friendless boy raised by four aunts.

Dacey’s short poems are delightfully devourable, like popcorn. Once you start reading what the mosquitoes have shared with him over the years from their ounce-sized repertoires, you will not be able to stop yourself from wanting more of his kernels; sometimes funny, sometimes sad, sometimes ironic:

Postcard

I left you

because I love you

so much.And the general

bombed the villages

to save them.

For a poet who can pull off 135 lines of iambic pentameter complete with rhythmic variations and a rhyme scheme that is always musical and surprising (see the title poem of The Deathbed Playboy, Eastern Washington University Press, 1999), it is instructive to read Dacey at the more spare, but no less captivating, end of his poetic spectrum.

One More Thing To Be Grateful For

Water comes

with no sharp edges.

Dacey explains in his author’s note that his impetus to write short poems includes the lineage of masters of concision like Robert Bly, Ezra Pound, and others, with heavy doses of Asian forms such as haiku and renga. The extra nudge to make brevity part of his own practice came, he writes, when he encountered a short poem by Bill Knott in the late Sixties called simply, “Poem”: “The only response/to a child’s grave is/to lay down before it and play dead.”

I am reminded of another short poem I read recently in Anthills V (Centennial Press, 2009) by Glenn W. Cooper called “Reconciliation”: “Like little boomerangs of hope,/her toenails in my ashtray.” This uncanny ability to tell an entire story in very few words is to be admired. Like his compadres in the art of the short poem, Dacey frequently uses the poem’s title to bring the story into focus:

Long Distance Relationship

The miles cross

their bare, muscular arms

and glower.

or

Suicide

I always liked

to be early

for my appointments.

In later sections of the collection, Dacey has grouped the poems into either short or long sequences of which he writes, “Given the autonomy of the poems so linked, their order within each sequence is immaterial, and poems could be dropped or added without particularly disturbing the whole.”

In these various sequences, he deals with such topics as the art of darning; pastoral snap-shots of rural Minnesota, the ruminations of a bored juror; a music-lover’s observations of Julliard students performing; and a half-comic, half-desperate view of aging: “The Skinny Old Man Pumps Iron.” One of the short poems within this group reads:

Getting buff

for the grave.

I laughed out loud at a poem called “Dress Code,” which is headed by the following note: “please avoid noisy fabrics—from guidelines for a Buddhist retreat.”

Please turn down the volume

of your socks.

and

A storm of polished cotton

was brewing, threatening

to drown out the song

of the silk undies.

ending with

A lone spool of thread

in the corner practiced

the discipline of silence.

Often, it feels as if you could turn these short poems inside out on themselves and into very fine riddles. Some are already presented as questions, and the “koanic” nature of many of the poems shines through:

Question for My Son To Answer

Are we children of the stars

or children of the spaces between the stars?

And what about the smoldering intimacies alluded to at the beginning of this review? How about this one:

Lines for a Headboard

Lights off or on? The lovers disagree.

She craves the dark. Romance. Where the soul sips.

He feasts on watching pleasure part her lips.

Oh, help, wise Candle, that says see, not see.

One of my very favorite poems in the whole collection is a triolet. The recipe for one of these, along with a wealth of other poetic forms, is to be found in Dacey’s epic bible of forms, Strong Measures, co-edited with David Jauss (HarperCollins, 1986).

Triolet for a Nude

Let be be finale of seem.

Wallace StevensYour parts all flow together,

There is no seam at all,

And I would follow where

Your parts all flow. Together

We’ll show how much we care

To let be be, for while

Our parts all flow together

There is no seem at all.

Mosquitoes are generally annoying little critters that buzz in your ear. Dacey’s short poems can certainly buzz, but there is nothing about them that is annoying. In fact

if these tiny poems are the operatic movements of mosquitoes, then I would like to sit down in a summer field at dusk and let the mosquitoes sing in my ear all evening.

In Mosquito Operas, there are many gems and many surprises. Like all good poems, these poems inspire, and may make you want to try your hand at writing your own mosquito operas, but poet beware. Writing short poems cannot be easy; certainly not as effortless as Dacey makes it seem.

To end, two from the series “Notes of an Ancient Chinese Poet”:

Write each poem twice,

once in sunlight,

once in moonlight.

and

Listen to the voice

of each dead poet

as if it were yours.

It is.

Lisa Vihos worked for twenty years as an art museum educator and is now the Director of Alumni Relations at Lakeland College. Her poems have appeared previously in Verse Wisconsin, and in Free Verse, Lakefire, Wisconsin People and Ideas, Seems, and Big Muddy. She is an associate editor of a new literary journal, Stoneboat, which made its debut in October, 2010. She resides in Sheboygan with her 12-year-old son.