Book Review

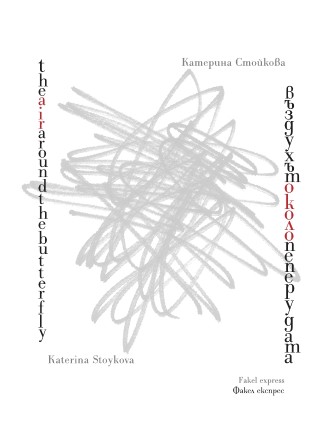

Katerina Stoykova, The Air Around the Butterfly, Fakel Express, 2009.[Visit the author's website to order.] $10

Reviewed by Judith Swann

"Otherworldly" is the best way to describe The Air Around the Butterfly, Katerina Stoykova's lovely first book. It is a Bulgarian-English set of facing-page translations, with the author providing both the original and the English. Published by the prestigious Fakel ("Torch") Express, and identified with the publisher's Post-Communist mission of bringing the Bulgarian reader closer to the "moral values and trends of modern civilization," it sings with a non-political panache that we do not expect to come out of the Balkans so soon after the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the strife all around the rim of the Black Sea from Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia to Kosovo and Chechnya. Bulgaria was far enough south that it did not suffer the worst of World War II and Stoykova's home town, Burgas (from the Greek word for "Tower") was, for some reason, never fully Sovietized. When Stoykova was born, then, it was into an oil-rich, fairy-tale resort town just down the coast from where Ovid lived in 8 A.D.

Stoykova immigrated to the U.S. in 1995 on an H1 engineering visa but stayed to do the arts. Her work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net Award and AWP Intro Award. She hosts a radio show for WRFL FM in Lexington, Kentucky—featuring appearances by Ursula K. LeGuin and Charles Simic—and she has a website.

One does not see a lot of facing-page Bulgarian-English volumes for sale at the local bookstores; but perhaps this book, which is both beautiful as an artifact and satisfying as a show of craft, heralds something new. The artwork by Inna Pavolvna on the cover and the subheads, with its long columns of text arranged like sutra scrolls, is worthy of the engineer for whose work they are designed. The pages are finger-pleasingly heavy and textured, a gracious shade of ivory, with the occasional red rubric you associate chiefly with illuminated manuscripts. It must have cost a fortune to produce.

The first several poems in the volume are autobiographical in that they portray the artist as a member of her family, her mother's mother's daughter, her father's peer. In the title poem for this section "My Mother Was Going to War," Stoykova presents her persona dramatically. "In her slippers / and cotton night-gown," she says, "loose / over the large tumors / my mother was going to war." The whole section is about 20 poems long, and it strings together one deft portrait after another, a sequence of mostly short poems.

Time

I asked Grandma

why she was crying.She told me that

my great grandmother Maria

her own mother

passed away."But that was last week!" I protested

frowned and pulled on her hand

to come play with me.Nobody Made Soup

My father and I were

drinking coffee, arguing

while Mom was coming

out of surgery."You make her soup."

"No, you make her soup."

I'm sorry I don't have the Bulgarian font so that you could see these poems across from the originals.

The second section, "E.T. and I Phone Home," are all about relocating. We meet the elderly female relative eager to move to the city ("the toilets are indoors") from the country with its "stock of wood." We see the boyfriend going off to the military ("his mother and father / waved goodbye to me"). But Stoykova is not a mere diarist, she is an alchemist. She turns to Hopi language to shine a light on the spiritual meaning of immigration:

Sus-toss

Sus-toss is a word in the Hopi language to describe the disease that people suffer when they move on to new lands.

Sus-toss is a disease that makes you not want the things you want.

It makes you not want to think about the things you want.

It makes you not want to talk to your friends.

It makes you not want to have any friends.It is the disease of living in a walnut shell

and spending all your strength to keep it closed...

The last section, "The Apple Who Wanted to Become a Pinecone," pushes the concept of identity beyond the Indo-Germanic relationship terms mother, father, and grandmother, beyond the sociology of the environment and into the self-contained. In "Loss," the poet tells us that if the butterfly "tries to be an ant," the world "loses a butterfly." Of course, we nod, this is true. It is a tautology, in fact. And is the creative process then a tautology? Not according to Stoykova. In the remarkably succinct "How To Write a Poem," Stoykova gives us a metaphor for the creativity of self-containment; she gives us both the thing and its nimbus:

How To Write a Poem

Catch the air

around the butterfly.

Judy Swann lives in gorgeous Ithaca, NY in a small house painted in Frida Kahlo colors. Her poetry has appeared in Lilliput Review, Verse Wisconsin, Soundzine and other places both in print and online. She is an Iowan who often visited Wisconsin in her youth.