Book Review

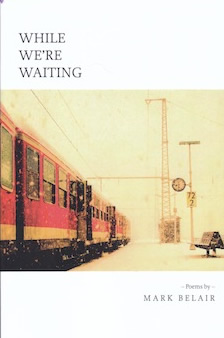

Mark Belair, While We’re Waiting, Aldrich Press, 2013

Reviewed by Tim McLafferty

In While We’re Waiting, his first full length book of poetry, we find that Mark Belair consistently mines the arc of his life, finding and connecting moments lived with steps toward gnosis. This knowing may be his, or ours, collectively, since what he sees is what we all may have seen, had we been looking.

Perhaps my favorite poem in the set is "Pull of Gravity." In its eight lines we find the sort of poetic reduction that paints clearly while meeting us halfway, allowing us to fill in details from our own experiences. Taken in one quick shot, this poem offers us image, motion, mother/child dynamics, poetic reduction, metaphor, and interaction between poet and reader.

Pull of Gravity

For a rocket to achieve escape velocity

from mother earth,it must travel a blistering

seven miles per secondor get sucked back down and,

flaming out, crash at sea.When I was a boy,

my mother was the world to me.

Space, clarity, sanity, and light—these are, to me, the four most immediate qualities of Belair’s poetry. This is not to say that he avoids his or our darkness, but his approach to its portrayal is unique to him. Certainly a poem like "Pull of Gravity" has dark connotations of the sort that could have filled a book in the 1970s, but confessional poetry isn’t for everyone, and often a peek is better than an eye-peeling reveal. In "The Lake," he again uses a very graceful metaphor, admitting both the need and function of inner darkness, and that it doesn’t necessarily require manifestation.

The Lake

The wooded lakeshore

slopes downhill

to the flat

planet of water

inhabited in depth, its glossy

surface offering to the sky

a moon-plain face, keeping from

the eye of the sun it needs

the darkness it needs

to keep itself

cool, wriggling, flowing, complete.

Belair has also included some of his longer prose poems— all set in lower case and using forward slashes to indicate the breath of phrases. This interesting way of setting the poem paints a lot of information onto the page while keeping us in the flow of the beat, even if the beat is that of spoken English. In "the orderly" we are introduced to six fascinating residents of the senior care facility that Belair worked in as a teenager, one of them is Mr. Hurley—

am i all right / mr hurley inevitably asked / should you meet him shuffling along on the arm of his expensive private duty nurse / am i all right / am i all right / you’re all right mr hurley everybody replied / then he’d smile with gratification / and say his other working sentence / thank god /…

Like many contemporary poets, some of his poems end with what might be called a final integrity—something akin to a coda in music leading to the ultimate chord. Belair is careful to not overuse this device, and it works perfectly in his poems of growing, which are told regardless of his physical age. The poem "Summer School" describes, in vivid detail, the neighborhood kids queuing up in line for the ice cream truck—filled with hope and expectation, only to find themselves with either stomach aches, headaches from the truck’s fumes, short of change, or dropping their ice cream by accident—

Then the truck, with a grinding of its gears,

jingled off, escaped wrappers

blowing into our tidy yards,

kids brushing pebbles and dirt

off treats they had dropped,

all of us struggling

with a vague, nagging sense

of the ambiguity of fulfillment

and the persistence

(we all knew we’d return, full of hope, when the jingling did)

of desire.

And in a similar capacity, a holy water font becomes a metaphor for faith in The Empty Church—

…this empty church uncannily

the same, only me changed from when

my raw need for faith first appeared

and I tiptoed up to dip my fingertips

in the high marble font of holy water

I couldn’t see, only feel.

And as an adult struggling to comprehend the disconnect between what we see and what we think we see, in "Tricks of Perception"—

I once caught my wife and my best friend whispering

intimately; whispering that stopped, without explanation,

when I surprised them by walking into the room.

The next week I walked into a surprise birthday party.Reaching off a ladder, I once saw

what looked like the ground itself

rising up to meet me.

It was, and it knocked me out.

To some extent, we all move forward with our destruction behind us, sometimes quite unknowingly. In "The Ice Cream Girl," the young and beautiful girl is, as far as she’s concerned, just selling ice cream. In viewing the empty shells of ice cream tubs tossed behind her and the long line of amorous suitors in front of her, we find a bittersweet allegory of the perils of courtship.

The Ice Cream Girl

I stood in a long line,

watching the pretty, ponytailed ice cream girl—who,

the year before, when we were both high school sophomores,

was mine—deftlydig the last of the butter pecan

out, leaving the once-solid, brimming tub

scooped empty and so light she just licked her

fingers clean and plucked it up and chucked itonto her growing pile of empties, and I felt

for all the little boys in line

craning their necks,

so eager to reach her.

Through writing what he sees around him, Belair’s poetry records and celebrates the act of living, and in these shared and common experiences, we may find ourselves drawn to his perspective, finding, in him, a dedicated autobiographer in possession of a sensitive and sympathetic eye. All together, While We’re Waiting holds 60 of Belair’s poems, and this review is merely a sample of what you will find there.

Tim McLafferty lives in NYC and works as a drummer. He has played on Broadway in Urinetown, Grey Gardens, and many other interesting places. His work currently appears in many fine journals, including Forge, Painted Bride Quarterly, Pearl, Portland Review, and Right Hand Pointing. Visit timmclafferty.com.