(di)Verse Wisconsin: Community & Diversity

by Wendy Vardaman and Sarah Busse

my feathers

sailing

on the breeze

the clear sky

loves to hear me sing

overhanging clouds

echoing my words

with pleasing sound

across the earth

everywhere

making my voice heard

—Ojibwe Dream Song (unknown date/ author) in Winter Nest: a Poetry Anthology of Midwestern Women Poets of Color, ed. Angela Lobo-Cobb, 1987

In 2009, we inherited an independent poetry magazine named Free Verse from Linda Aschbrenner, who had published it on her own from her living room in Marshfield, Wisconsin, for 11 years and 100 issues. Free Verse was born out of Aschbrenner’s writing group and its frustration at the lack of publishing venues for its members. Aware of the biases against poets who did not belong to the academic community and who did not necessarily have degrees or awards behind their names, Aschbrenner collected poems from the group and photocopied them, handing copies out to friends. Poets being what they are, they shared these simple monthly documents, and Aschbrenner started to receive submissions from others as well. Thus began a magazine which became something of a fixture in the indie press scene, and a means for Wisconsin poets, particularly, to feel part of a community, as she shared not only poems, but also the knowledge of poets with one another.

Belonging became important to both of us when we moved to the state in 2000 and 2005, respectively. As writers know, especially when unattached to universities or other institutions, it can be difficult to find community in a new place. At home with children, writing independently and isolated from peers, contacts and adult conversation, we recognized on a personal level the important role that an academically unaffiliated venue like Free Verse could play. When we became its new co-editors, we didn’t want to lose that sense of belonging, even as, in 2009, we discussed other changes, including a new name, Verse Wisconsin, that referenced our identity as a place-based community of poets, even as we sought to extend our reach by creating a new, online component for the magazine.We wanted to cross boundaries in all kinds of ways: print and online, intellectually rigorous and community based, small-town friendly and artistically and creatively ambitious, and to accomplish this goal we added another key concept: diversity. Community and diversity are the twin poles by which we navigate, and although there is at times an uneasy relationship between the two, we believe the tensions inherent therein help us to create a richer publication.

But what do we mean by diversity? Verse Wisconsin strives to include variety with respect to age, race, class, gender (and all its contemporary complexities), geography, occupation, poetic genre and aesthetic. If the mix we seek isn’t exactly (or only) urban, we could certainly call it polyglot, a heady, giddy, slightly anarchic endeavor that feels many days like juggling, or running a three-ring circus.

How do we know if we’re achieving our goal, providing a space for truly diverse poets and reaching out to diverse audiences? Well, like any conscientious editors, we count, we track, we compare our poet pool to the broader populations in the state, in the region, and see how we match up. We study. We research. If we find we receive content from, say, 60% women, but accept them at the rate of 40%, we would ask ourselves why and launch an investigation. When we are aware that some other kind of poetry has a base in say, Madison, we try to find out more about it and its practitioners and understand why our publication isn’t drawing their work. Maybe we make changes. Maybe we attend new events created by other groups. It doesn’t always work, but we make attempts, reaching out to a variety of organizations, as well as in to university groups that may exist apart from the community.

Redressing the Balance

What I want to know is

Do you really want your mother and father

in a factory all those years?

Let alone America selling torture devices world-wide

since l983,

Let alone the government injecting us with radiation

without our knowing,

Let alone enough bombs to create a World War II every second

for a century,

Let alone New York City using more energy in a minute

than Wyoming in a week,

Let alone the leading bestseller a book

on how to kill yourself,

Let alone the $750,000 it cost to kill

each soldier in the Gulf War,

Let alone veterans throwing their Medals of Honor

on the White House steps,

Let alone TV devotees with l000 channels per set,

Let alone before Christ ever dreamed he needed to be crucified

this Sequoia had seen 2000 years go by

without once believing there was

a better world than this

and only by dying could you get there?

Emphasis is on selling one's time.

Emphasis is on timetables and deadlines.

Emphasis is on speed-at-all costs.

Emphasis is on planned obsolescence.

Emphasis is on becoming a billionaire.

Emphasis is on steel-jawed leg-traps.

Instead of foundering dumbfounded,

we outsmarted ourselves—

The names of the days and months were invented.

The number of numbers on the clock was made up.

The existence of money and having to earn it

was made up.

No wonder we're floundering when

no wonder is why we're floundering!

Our own planet is the planet

We daydream what it might be like to land on

All starry-eyed realizing we're from Outer Space

and have come to teach Earthlings how to love.

Eternity is not a rat-race,

Eternity is not a traffic jam,

Eternity does not punch in on a timeclock

or exist from paycheck to paycheck,

Eternity has no lunchbucket or thermos,

Eternity has no safety shoes,

Eternity has no second hand or hour hand

or numbers that go around in a circle,

Eternity doesn't enter the lottery,

Eternity doesn't merger its debentures,

Eternity doesn't calculate its net worth

on a pocket computer,

But Eternity is so vast

in the endless and infinite reaches of Eternity

it needs now and then,

a poet whose full-time job is

silently observing by candlelight

girls having dreams in their sleep.

—Antler, Milwaukee, WI

110 “It’s Political” Issue

Beyond inreach and outreach, comparison and measurement, we also question whether diversity, like justice, is something that can be “achieved” or is better thought of as a goal, an ideal, something on which we fix our eyes and frequently stop to ask ourselves: How are we doing? Can we do better? How do we better? With whom do we engage in order to help us do better? Perhaps, for us, “diversity” has become a code word for a questioning stance, a willingness to listen to others’ stories, divergent narratives, experiences, other silences, for that matter. By remaining open to interaction with others—poets, artists, organizations, we gain greater awareness of our own place in the community: two middle-aged white women with advanced degrees, families, privilege that we are aware of and no doubt sometimes fail to register, and too many volunteer jobs.

As important as the what of diversity for Verse Wisconsin is the why. Why not, as poets and artists, stick with our own groups, whether that is a university-based creative writing program, or a different socially-defining characteristic like youth, or some aesthetic principle, such as “plain speaking” or experimental? First, we believe that diversity complicates narrative. As poetry itself insists on complexity of language and thought, working against the simplifications of the marketers, the dishonesty of mainstream media, and the voiding of meaning common in political speech, true diversity works against the corruption of cultural narratives by offering internal critiques through multiplicity, something we have tried to illustrate with the Verse Wisconsin poems interspersed throughout this essay. We also believe that diversity—of ideas, of style, of aesthetic, of voice—helps us to grow artistically. The creative poetic work of those we don’t normally encounter—whether that is hip hop or postmodern theater or The Onion or people in nursing homes—can, if we take it seriously and engage deeply with its aesthetics and artistry, provide a means to see what we do differently and to change through the encounter. That this artistic encounter has, we believe, a further role to play in creating a less segregated, less stratified, more democratic society as well as a more interesting one is perhaps idealistic, but we wouldn’t do what we do if we didn’t believe that.

Missy at Peace

Arms extended upward, muscles taut,

thumb firm against tack, posters

scholarly blue, searing green: peace

meeting Thursday. Up these stairs,

down this hallway. Here. This room.

Chicago rally Saturday. All in favor?

Hands low, easy, on the steering wheel.

Halfway to the Loop, she reaches for a CD,

long fingers, trimmed nails, clean,

curved, skimming the edge, the center.

You’ll like this.

Palm flat to tap the beat, then double-time

laugh-singing. Dreaming. Maybe after graduation

Palestine. To help with the harvest.

Olives growing ripe in the hot sun. For now

stone, steel, glass, on the way

Daley Plaza, untitled Picasso.

Missy’s hand up to her face,

she tucks hair behind her ear.

Where are the directions?

When will we get there, Missy?

We’re on Michigan Avenue.

It’s impossible to get lost.

—Margaret Rozga, Milwaukee, WI

110 “It’s Political” Issue

These multiple voices are welcome to us as individuals, as well as artistically: writers need community. We need the support of fellow writers as well as the challenge. We provide audience for each other and produce each others’ work, making place and space for our collective words and texts. In the current political landscape that is Wisconsin, we are particularly aware of the importance of a thriving grass roots community of producer-writers, or publisher-editor-poets, because that is all we have. With no public support at the state level, those of us outside of academic and other institutional frameworks have precious little to keep us going.

Steering by these twin stars, community and diversity, we developed our mission:

Verse Wisconsin publishes poetry and serves the community of poets in Wisconsin and beyond. In fulfilling our mission we:

- showcase the excellence and diversity of poetry rooted in or related to Wisconsin;

- connect Wisconsin's poets to each other and to the larger literary world;

- foster critical conversations about poetry;

- build and invigorate the audience for poetry.

We’re aware that each of the terms in that statement can be complicated, and we try to do that work, asking with each issue we publish: Who counts as a “Wisconsin” author? What counts as “Wisconsin” poetry? What is a poem and who gets to be a poet?

We are all too aware, for example, that there is a certain nostalgia, even sostalgia, sadness about the loss of places with which we are familiar, connected to the very idea of Wisconsin or Midwestern poetry, but we resist the notion that these are inherently pastoral categories, even as we include poetry responding to rural themes and images within our pages. And poets writing about rural places do not, necessarily, write with any one style or agenda, with one set of connotations, any more than Midwesterner poets writing about urban spaces do. If anything, we look to incorporate work from all populations that thoughtfully engages with a range of places, or with multiple or mediating places, and may have more in common than work of either rural or urban poets that relies on either easy abstraction or unexplored assumptions. We are uncomfortable, for instance, with projects like “Our Wisconsin” that don’t actively problematize nostalgia and define, before engagement, the terms of the writers’ experiences as an idealized past. We are likewise uncomfortable with events meant to suggest an open door that skew towards younger work or academic work, on the assumption that those poets best reflect contemporary poetry.

Showing You Around

A lion tamer lives just down the road.

He’s eighty. Flaming hoops blaze daily;

whip in hand, he waves. Next stop

is the fiberglass badger squatting on

the roof of Uncle Bob’s Exotic Dancers.

You agree, it’s all I said it would be

as we skirt an Air Force base, abandoned

since the seventies, surrounded by woods

no one hunts in. My cousin saw a UFO

there once, parked in the starry night air.

Lightning always strikes behind the house.

I think a flying saucer’s buried there.

Mom used to blame the lightning on

that patch of clover by the water pump.

Some of them have seven leaves. She told me

all that luck draws heaven’s jealousy.

—Mike Kriesel, Aniwa, WI

104 “On the Road” Issue

At Verse Wisconsin we are open to various definitions of poet and poetry, from spoken word and visual work, to video and verse drama, to prose that incorporates poetry or that is poetic, to dance and musical collaboration. And we are also aware that the writers who often need the most support, from those in prison, to those who are homeless, to the young and those in assisted living, have access to the least resources, and are literally invisible to most of us. How do we support and recognize these writers? How do we find them?

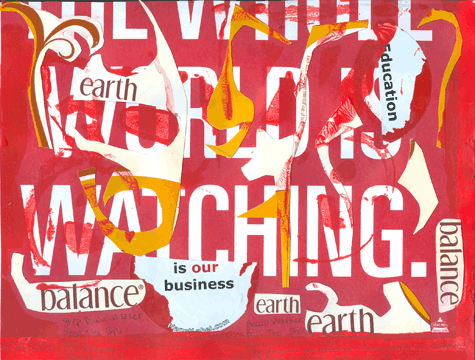

World Watching, by Matthew Stolte, Madison, WI, “Main Street” Issue

As we have diversified the notions of Wisconsin, of poet, we have diversified content by increasing the amount and types of prose we publish, right in among all the poems: our “Wisconsin Poetry News” column promotes the projects of groups (rather than news from individual poets) and pays attention to service and activism of poets across the state; we include interviews, craft essays, personal reflections; we encourage (though we don’t often receive) hybrid prose-poetry work; we encourage readers to become book reviewers, and we mentor new reviewers, creating, we hope, readers akin to Virginia Woolf’s “Common Reader” and a group of reviewers whose backgrounds, opinions, and types of expertise are as diverse as the poets they read. Our interviews allow us to reach out to poets inside the state who don’t always see themselves as participating in a community, as well as those living out-of-state who are nevertheless connected to Wisconsin in substantive ways, inviting them to share their work, their vision of poetry, and to think of themselves as connected to the region.

As a hybrid print-online magazine, Verse Wisconsin creates print, as well as a virtual, space, and its community occurs within, and across, those spaces, as well as in real time. The print magazine uses a larger, 8 ½ x 11 format inherited from Aschbrenner and places multiple poems (3-4) on each page, which means that 6-8 poems typically occupy a 2-page spread, an unusual decision in poetry publishing. During layout, we ensure that poems sharing space also share themes, imagery, or some other commonality, or even difference, which will create conversations among them. It’s not a minimalist aesthetic, instead stretching toward something like “maximalist.” Another community-driven feature is the inclusion of every poet’s name on the front cover. Rather than choose two or three or four “big names” to feature, we prefer to print a visual representation of that issue’s community.

Angles of Being

It’s all angle after all.

What we see

and miss.

The leaf bird

limed and shadowed

to match

every other

green upturned hand

blooming on the August tree

Indecipherable

even when wings flutter

like leaves in breeze.

Or the silhouette

dark and curved

on the bare oak.

Beak,

parted tail,

each mistakable

for knot

branch

or twig.

Only if they exit the scene

unblend

isolate themselves

against too blue sky

does the game

of hidden pictures

end.

Ah, angles.

Tell all

or tell it slant.

What we

dream

appear

or inverted

seem to be.

—Kimberly Blaeser, Milwaukee, WI

107 Earthworks Issue

Online, we offer different, but related, content. We include poems around a specific theme or call, news, essays, interviews, reviews, special sections and features on projects, partnerships, and creative reactions or reflections coming out of events such as the annual summer Hip Hop Educators’ Institute at the UW-Madison. Publishing online allows us to embrace a wider diversity of formats , including visual poetry, songs, music/text mashups, audio and video of poets performing their works. We have published poems and prose around a wide variety of topics, too, and our online calls range from poetic form to political poetry, verse drama to ecopoetry, and are often designed around a particular collaboration, or to try to create new partnerships. Our political poetry issue, for example, was timed in conjunction with a Wisconsin Book Festival at which we coordinated an event involving community- and university-based poets responding to dynamic work by poet-performers in the First Wave Hip Hop Learning Community and brought Kentucky Poet Laureate and co-founder of the Affrilacian Poets, Frank X Walker, to engage with a variety of Wisconsin's poetry communities at the festival.

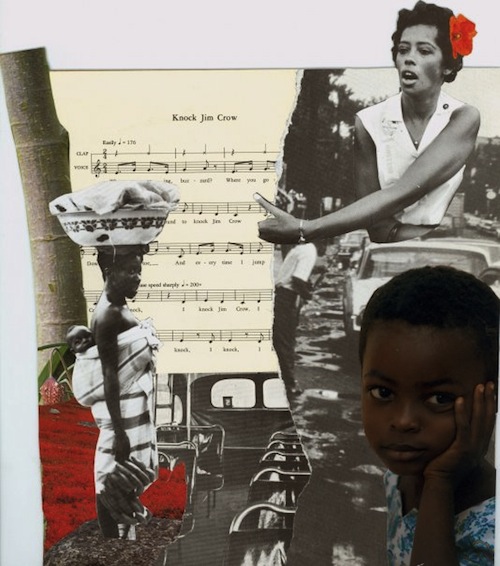

Waiting, by SaneleVox, 109 “It’s Political” Issue

Social media likewise offers more possibilities to reach a wider audience geographically, while simultaneously, we hope, building knowledge of each other and community: both Facebook and a YouTube channel enable us to feature content, to draw a larger group of readers to our site, and to give poets and writers yet another platform for their work. During the protests in Wisconsin, we simultaneously published a protest poem issue as “notes” on Facebook and as a special online “Main Street Issue.” We’re able to engage with a broader audience of poets and thinkers through social media, to learn from them, and hopefully to participate in such transformational interactions online as well as in person, as was the case with the Main Street work.

Around the edges of the magazine, increasing in frequency, we have held readings, panels, presentations, conversations, and other kinds of events, which invite people to engage with poetry and questions around poetry in person. These events have, themselves, driven both our thinking and the content of future issues, and have evolved from marginal to central features of our process and product. Along the way, we’ve come to believe in the importance of face-to-face conversations, with and without poems, as a means to bring people together, discovering new ideas and questions, while building relationships and promoting public poetry, and we also believe in the importance of attending a range of events conducted by other groups in various spaces, from slams and festivals, to symposia and lectures, all of which are also part of the discovery, the research-driven process for locating and connecting poets.

Thin Air

Trapped by a bend

in the basilica, a bird

hums inside at the humming-

bird outside glass trilling

against its frenzied whir.

A man I’ll never stop

loving climbs the wall,

hovers on a sill stretching

to grasp at anxious

reflections. How many

heartbeats to escape inside

the outside of joy? To turn

a green wing toward

his dark palm closing

off light? Lightly palms globe

the terror song, carry it

to a garden like a sacred stone.

On a holy hill that keeps

our crutches, fingers unfurl

in a lemniscate of wings.

—Brenda Cárdenas, Milwaukee

109 Community Issue

Our mission has undergone a parallel change, as our emphasis has shifted toward conversation, activism, and transformational circles, and away from traditional publication. But publishing is itself another word to stretch, re-interpret, and to reinvent playfully and thoughtfully. Increasingly, we are involved in efforts to publish in new and unexpected places and spaces, putting poems into our Verse-O-Matic vending machine, on buses, bicycles, shoes, postcards, and road signs, as well as in magazines and books, as both Verse Wisconsin and Cowfeather Press. We have created colorful broadsides of all shapes and sizes, co-edited a Wisconsin Poets’ Calendar, and introduced poetry into Madison’s City Council meetings. Current projects bring poems to an art gallery for a celebration of art about protest; to a playhouse for display in response to a production; and juxtaposed with composting demonstrations and lectures on soil science in readings and a poetry (de)compos(t)ing station. Over the past five years, we have found that we do our best, most interesting work in partnership with a wide variety of groups, and to date we have engaged in a variety of joint endeavors with over thirty groups, including Wormfarm Institute, Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, UW’s Office of Multicultural Arts Initiatives (OMAI), Poetry Jumps Off the Shelf, Forward Theater, Writers in Prison, the Wisconsin Humanities Council and Book Festival, as well as literacy groups and libraries, retail spaces and nonprofits.

I Force Myself Upon the Soldier

All the words are resting.

The soldier across from me

binds her mouth, but I

push them in past

the ticker tape and the winding

clock tongue, past my own

fears sitting pretty like cared for

teeth of the rich.

My eye close to her–I

ask why why and why.

L didn’t know her name

before he died. This soldier who

hides her name behind a

rifle. I search her memory for

you.

I have followed to this seaside

town where there are no people.

I hear no snoring or sounds of love.

The soldier leans across from me, does not want

the shadows dancing upon her sensible

face, but the words will not rest.

They take shape and stomp.

—Ching-In Chen, Milwaukee, WI

* The title is taken from Sarah Gambito’s poem, “Kundiman.”

109 Community Issue

As we discover the centrality of collaboration to our operational method, of partnership to our process, we explore the relation of word and world, and realize that, at its most interesting, the role of editor allows us to be—rather than gate keepers or canon makers—event planners: even a print magazine or book has an ephemerality about it. Embracing, engaging with transience, rather than resisting it, allows us to do other kinds of work, and to ask other kinds of questions. Rather than worrying about and trying to create and maintain an institution, buildings, permanent infrastructure, we can emphasize process, relationships, and transformation, asking ourselves: Who will we invite to the party? What sort of gathering will it be? Does everyone look like us? Think like us? Sound like us? Is that interesting? What other parties are going on around us that we might think about attending?

Cruzando

Era un frío de aquéllos

El Coyote nos dijo:

piensen en su familia

cuando se trepen,

la cara de gusto

cuando sepan

que ya están del otro lado.

La noche se nos vino encima

y no tuvimos tiempo de pensar en nada.

Fue a las tres de la mañana

que escuchamos a ese dragón

de hierro y humo,

golpear nuestros párpados,

golpear la tierra con su larga cola.

Fuimos cuatro los trepados

cuatro los suertudos.

El frío escaló nuestros huesos

con sus clavos y aldabas.

El Coyote nos dijo:

¡A dos horas de aquí!

¿Por qué no?

¡Una cerveza para empezar

bien la mañana!

Esa noche

me detuve frente a los adobes de la casa

y las vigas llenas de abismo,

me detuve frente al triciclo de nuestro hijo.

“No confíe en el coyote

pegue los ojos en su espalda.

No se duerma, el Coyote espera

el momento oportuno para dar la zarpada.

Si se duerme lo saquea y lo abandona

en medio de la chingada.

No se confíe

No se confíe”

A las seis de la mañana,

muertos de frío,

con la oscuridad en los ojos

descendimos del tren

como pasajeros de lujo

despacio por el barandal,

con las manos esposadas,

y los brazos en la espalda.

Una gota de hielo como luz

colgaba de una rama.

Crossing

It was one of those cold nights,

the Coyote said to us:

Think about your family

before you jump on the train,

their faces of joy

when they know

that you are on the other side.

The night fell over us and

we did not have time to think about anything.

At three in the morning

we heard that dragon

of iron and smoke,

we felt it strike our eyelids,

strike the earth

with its long tail.

We were the four

lucky ones

who got on the train.

The cold scaled our bones

with clips and bolts.

The Coyote said to us:

Two hours from here! Why not?

A beer to begin the morning well!

That night I stopped

in front of the bricks of my house

and the beams full of abyss.

I paused in front of our son’s tricycle.

Do not trust the Coyote.

Keep your eyes on his back.

Do not fall asleep. The Coyote waits

for the right moment to strike.

If you close your eyes,

he will pick you clean

and abandon you

in the middle of nowhere.

Do not trust him.

Do not trust him.

At six in the morning,

frozen to death,

with darkness in our eyes,

we descended the train

like first class passengers

slowly along the rail,

handcuffed.

A drop of ice shone its light

from a new branch.

—Moisés Villavicencio Barras, Madison, WI

110 “It’s Political”