Book Review

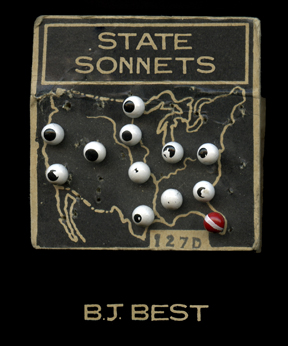

State Sonnets by B.J. Best. Buffalo, NY: sunnyoutside press, 2009. $13.

Reviewed by Karla Huston

In the spirit of those famous Hope/Crosby road movies, in the soul of romantic comedies like When Harry Met Sally, which is a road movie, as well, and in the shadow of the writing of Kerouac and Shakespeare (with a nod to Petrarch), BJ Best presents readers the best of both the road and romance in his collection of State Sonnets.

“— this was before i knew how things cleave apart. / this was before i knew what’s programmed in the heart.” Written with the wry resignation of someone who’s been-there, done-that, Best offers poems about nineteen states and a couple of Canadian provinces, not to mention Puerto Rico and a selection of places like a cave in South Dakota or Niagara Falls (which is located in both the U.S. and Canada), plus a nebulous location where the narrator “ain’t got no cigarettes” and is “a man of means by no means”. Most are love poems and most read like a travel journal full of sites and secrets of love, found, and mostly a lot of love lost. Poor guy. But what can you expect when the man doesn’t notice his woman’s “breasts and butterfly barrettes / … for a week and a half”?

Clearly the vehicle Best uses to travel his postcard roads is the contemporary sonnet, offering only minor homage to Shakespeare or Petrarch’s rigid rules. Best plays with stanza and line, syllable count and iambics leaving only one sonnet to use the traditional hanging indent on the last couplet. Some of his lines measure metrically ten beats per, but more often Best’s metrics percolate along, suiting the organic needs of the poem, making his rhythms never predictable or boring.

Best is able to find unusual or unexpected rhymes: choices like “tonic and cyclonic;” “brazil and until;” “humidity and proclivities;” “ankles and thankful.” “[S]o I lost her. so water eats stone. / so mammoth becomes a synonym for alone."

He also often juxtaposes more decorative Latinate words against simpler, more in-your-face Anglo choices. For example:

…

like a dead weight, my rusty insect of a car

locked in sleet. it was the city of margaritas

and hemingway—no, she said, jimmy buffett.

her bones hummed hard when he sang, sweet señorita,

won’t you please come with me. i said no, and tough shit.

or

…

you know there’s a thin fleck of time when all

the ripples turn tiger, orange and black

as moonrise, dappled as an old deck

of cards, the trees

extinguish themselves into sleeves …

In fact, his casual rhetoric reflects contemporary sonneteers, Kim Addonizio and Philip Dacey. Both are noted for using formal elements in their poems. Best, too, uses a modern voice, an informal language that doesn’t trample the reader with its sonnet-ness. And like the sonnets of Addonizio and Dacey, the reader isn’t aware that these poems are sonnets unless s/he takes the time to counts lines or syllables.

But where Addonizio, for example, excels is her daring risks with content which reflects the narrator’s angst and anger, sex and sensuality or often the deep and sometimes disturbing questions about being human. In her poem “The Sound” from The Philosopher’s Club (BOA, 1994) the narrator considers the sound suffering makes. “It’s shy, it’s barely there. It never stops.”

Dacey takes the same kinds of chances, writes with the same kind of power and sensuality —whether he’s a mid-westerner encountering the streets of New York or an aging lothario out for a ride with his lover when discovering her “Leg” (from The Adventures of Alixa Doom, Snark 03) a poem which opens, “Driving at night, I reached across for the knee / your skirt failed to cover /” and ends with, “The hand that writes this, held there, burned and burned.”

Best’s narrators don’t burn so much as simmer, but, perhaps he comes close to Addonizio or Dacey’s kind of depth when he offers readers a sonnet which echoes (some of) the last word of each line, a technique which creates additional tension, an intensity which is sometimes absent in his other love sonnets: “to / spite / me / you’d / settle / in / a city / of / seahawks / and / rain? / -- of / course.”

At the heart of these poems is that great philosophical trope:

love, love, LOVE. “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways,” says

Browning. “My mistress eyes are nothing like the sun,” complains

Shakespeare. In Best’s poems, readers find the same proselytizing and

pining, the same dead pan whining and winsome hope as the best of the

sonneteers. Unfortunately, even though he is a poet, Best doesn’t

always get the girl or keep the girl or even want the girl after he has

hauled her across a dozen states and a few provinces. In the end,

he is so often resigned.

i rattled the change in the console,

watching my reflection do the same.

i said failure was better than trying,

but didn’t mean it, as if that could console

you when you couldn’t stop saying her name.

Finally, marry these sonnets with the smart art and photography of Kevin Charles Kline, and readers get the best of all worlds and a road trip where the romance is as certain as the turn at the top of the next hill.

Karla Huston is the author of six chapbooks of poetry, most recently, An Inventory of Lost Things (Centennial Press, 2009). Her poems, reviews and interviews have been published widely.